By Suzanne Woolley

Aug. 4, 2022

First a pandemic, then a bear market, and then the highest inflation in four decades … and now the word on everyone’s mind is “recession.” As in: “Are we in one or not?” We’ve had one classic sign of an economic slowdown: two quarters of contraction in US gross domestic product. But that’s been accompanied by healthy wage growth and employment and continued consumer spending. Complicating the picture still further, measures of consumer confidence are way down as people face rising prices for everything from gas to housing.

Illustration: Nichole Shinn for Bloomberg Businessweek

Financial writer and social media influencer Kyla Scanlon has called this a “vibecession,” a period in which “the economic data says things are okay, but people aren’t.” In this topsy-turvy environment, what appears to be good economic news could turn out to be bad. Signs of strong growth will influence how much the Federal Reserve decides it has to raise interest rates, leading to higher costs on credit cards, mortgages, and car loans—and tougher business conditions that could lead to job cuts.

What do you do to prepare? If a recession were simply a matter of falling stocks, the answer might be: not much. Anxiety about the economy is already reflected in asset prices, and it’s hard to time market turns. But if a bear market is something that happens to your stocks, a recession is something that happens, specifically, to you. To your job security, your earnings, and your household budget. It makes sense to account for that in your personal balance sheet and your portfolio.

● Review your spending patterns and emergency funds

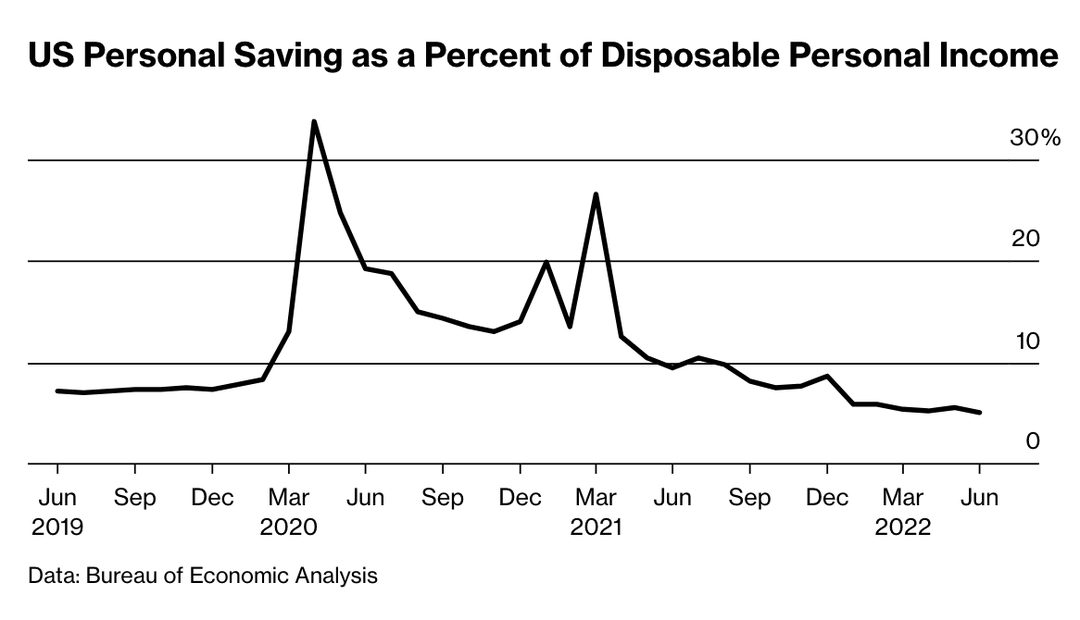

Watching what you spend is the most basic item in planning, and you may think you’ve already got this one covered. But the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath have made everyone’s budget a little weird. In the worst phase of the lockdown, many households built up a cash cushion, thanks to stimulus programs and just not leaving the house. With that additional money, you might have added new expenses, such as ride-hailing services to avoid mass transit or pricier broadband and subscription services. Meanwhile, people resuming pre-pandemic spending patterns—booking flights, fueling up for commutes, or eating lunch out again—are finding that all this stuff has become more expensive.

True, wages have risen as well, but not fast enough to keep up. The Consumer Price Index increased 9.1% in June compared with a year earlier. And the savings rate among Americans is now the lowest it has been since 2009, according to Commerce Department data.

It’s painful, but higher inflation means you probably have to beef up your emergency savings. Financial planners generally say three months’ to six months’ worth of expenses in a backup fund is a minimum. Wealth adviser Melissa Weisz of RegentAtlantic says she ideally wants to see clients with one year to two years’ worth of expenses in cash. Although the pandemic recession in 2020 was brief, the Great Recession of the late 2000s lasted about 18 months.

Savings accounts are losing money after inflation. But the point of an emergency fund is to buy yourself some breathing room in a recession, not to pile up interest. And rates are getting a bit better. Online bank SoFi offers 1.8% on savings accounts that use direct deposit, and Marcus by Goldman Sachs recently bumped up its online rate to 1.5%.

Not all emergency money has to be instantly liquid. If you can set more than a year’s expenses aside, certificates of deposit available at some online banks are paying 2.5% or more for 12-month terms. You could also take some of your longer-term cushion money and invest it conservatively in ultrashort-term bond mutual funds.

Series I savings bonds available online from the US Treasury can get you much higher rates. I bonds are tied to the CPI and currently pay 9.62%. The rate changes every six months from the date of initial purchase. You have to hold for at least a year, and if you sell before five years, you’ll forfeit the last three months’ worth of interest. You can generally put only $10,000—or $20,000 for married couples—in I bonds each year, plus some extra at tax time if you accept paper I bonds as part of your refund.

● Look at your equity risk

Making drastic moves in a portfolio is rarely a good move, but being fully aware of what risks you’re taking is smart. If a high equity stake is making you anxious, you can rebalance or just start whittling down that exposure by reducing the allocation in your future contributions.

If you use target-date funds in your 401(k) retirement savings plan, now’s a good time to get more familiar with how your money is being divided among stocks, bonds, and other assets. Target-date funds set an allocation based on your assumed retirement date, and gradually taper down the risk over time. But a recession has a nasty way of causing people to retire sooner than they expected. Christine Benz, director of personal finance at the research company Morningstar, worries that some older investors fall into “equity complacency.” Those who have invested in the markets for a long time know that markets usually bounce back. But later in their careers, they may not have enough years of earnings ahead to make up for a big loss.

If your portfolio is feeling a little too equity-heavy for comfort, you can take things down a notch by gradually moving money into a portfolio with a retirement date five years earlier. Running the numbers on what your finances would look like if you had to retire at 62, rather than 65 or 67, may give added incentive to save more.

Young investors may also want to weigh the pros and cons of holding a big slug of equities. The conventional wisdom is you can be aggressive in your 20s and 30s because you have so many years ahead of you. That view was weaponized by zero-commission trading apps during the meme stock era. But time to retirement isn’t the only factor—consider job security. In a recession, young, risk-loving investors could find themselves hit with a double whammy of falling savings and lost work.

Rob Arnott, founder of asset management company Research Affiliates, recommends that young workers invest defensively until they have enough money that they know they won’t need to touch part of it for several years. (If you have a full emergency fund, you are most of the way there.) The ideal risk stance is “to take low risk early in your career, high risk tolerance in mid- and late career, and de-risk about five years before retirement,” he says.

● Consider more stable companies

Once you have your emergency fund and asset allocation in order, you can think about the kinds of stocks you own. For most people, a diversified portfolio built around index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds will still do the trick. Their low costs usually give them an edge over active stock picking. Last year, almost 80% of domestic equity funds trailed the S&P Composite 1500 index of the broad US stock market, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

But if you prefer to fine-tune, there are reasonable ways to add stability to your portfolio in bumpy times. For example, you can tilt toward shares of companies that have the cash flow to pay dividends. Three dividend-focused ETFs are among the top 10 in terms of investor inflows this year.

As this shows, many investors have already moved into traditionally defensive stocks. Consumer staples and utilities stocks “are pricey now because everyone is piling in,” says Weisz. She recommends that investors broaden their scope to look at consumer goods and health-care companies, too. The sweet spot for Weisz is high-quality US large-cap stocks with sustainable or low debt levels and sustainable dividends. She also likes investment-grade bonds, whose average yield is now 4.35%.

● What not to do

Benz worries that people might be tempted to file for Social Security benefits sooner than they might have otherwise done because they don’t want to sell stocks into a down market. But Social Security is one of the only relatively secure income streams many Americans will have in retirement, and the rare one that is adjusted for inflation. So the advantages of waiting until at least full retirement age—which is 66 or 67, depending on year of birth—can be big. Those who wait even longer can reap the 8% increase in benefits for each year after full retirement age up to age 70.

On a more basic level, “a massive way to help yourself navigate a recession is to keep emotions in check,” says Nicole Sullivan, co-founder of Prism Planning Partners. “If you’re financially able, it could be a good time to continue or even increase your savings rate while asset prices are lower.”

© 2025 Bloomberg L.P.