By Josh Zumbrun

July 21, 2023

A pair of optimistic headlines in recent weeks suggest consumers are beginning to shrug off higher interest rates, the inflationary surge and recession fears—and feeling confident again about the economy.

Surveys that gauge the mood of U.S. consumers ask about current economic conditions and expectations for the future. PHOTO: SPENCER PLATT/GETTY IMAGES

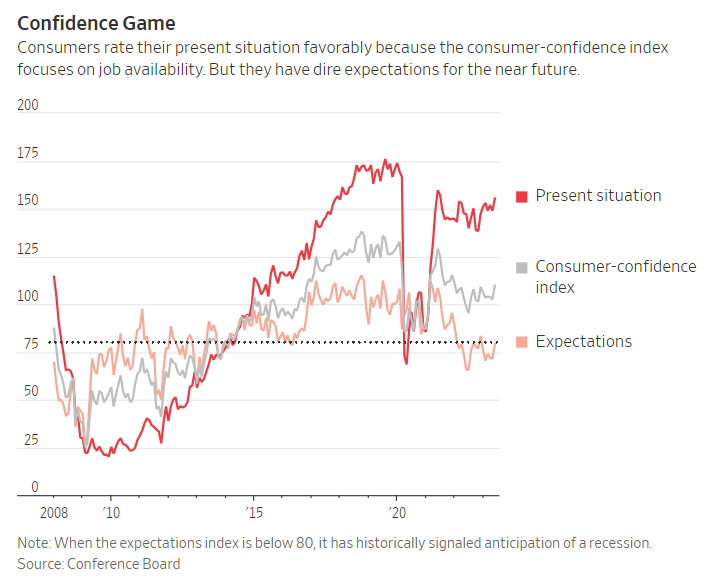

The Conference Board, a business-research nonprofit, reported its measure of consumer confidence in June climbed to its highest level since January 2022. The latest reading last week from the University of Michigan’s index of consumer sentiment was the highest since September 2021.

These are the two best-known gauges that seek to capture the mood of U.S. families and turn that frame of mind into numbers that we can track over time. The idea is that to really understand what is going to happen in the U.S. economy, it doesn’t suffice to know if people have jobs, whether their incomes are up, or what the stock market is doing—you need to know how they feel.

But a closer look at the numbers behind consumers’ moods paints a more complicated picture than the simple story that things are the best in a year and a half.

“I don’t think we’re out of the woods yet,” said Joanne Hsu, the director of the consumer surveys at the University of Michigan.

The University of Michigan and Conference Board measurements are based on longstanding surveys—Michigan’s since the 1940s, and the Conference Board’s since 1967. The readings have garnered regular headlines for decades in the financial news that tracks the ups and downs of consumers. Both indexes involve five questions—two about current conditions and three about expectations for the future.

To consider the differences in the measures, think about how you might respond to the questions.

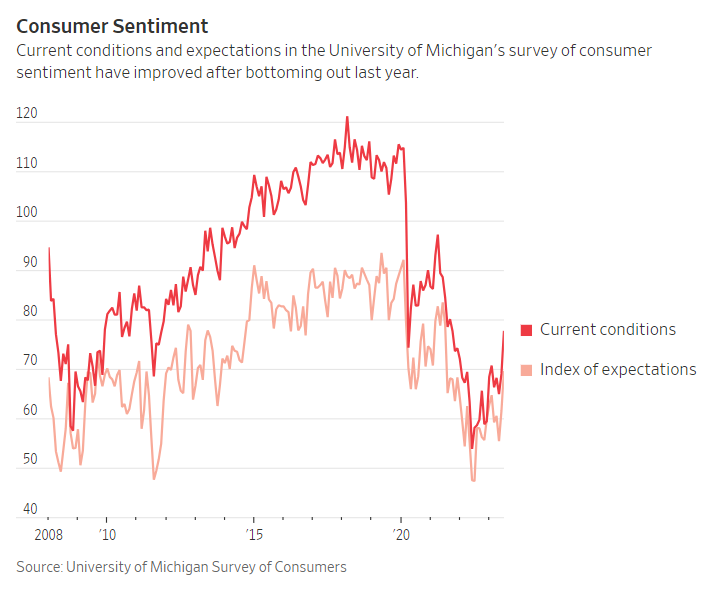

For current conditions, the Michigan survey asks people if they are “better off or worse off financially than you were a year ago” and then asks if it is a good or bad time to buy “the big things people buy for their homes—such as furniture, a refrigerator, stove, television, and things like that.”

These questions naturally prime a person to focus on inflation and prices. For the first question you might think about whether your wages kept up with inflation, and you might think about what stock prices in your portfolio have done. For the second question you would probably think about whether the items are expensive, or, in recent years, about the supply-chain problems that plagued many such purchases.

The Conference Board primes respondents to think about business activity and jobs, asking people how they would rate general business conditions in their area and whether “available jobs in your area” are plentiful or hard to find.

A year ago, Michigan’s measure of current conditions was clocking some of the worst readings in its history, while the Conference Board’s measure was actually fairly strong. Business activity was surging and jobs were plentiful and the questions don’t necessarily prompt consumers to contemplate inflation.

Then, both surveys also ask a series of questions about the future. Michigan asks if you think your family “will be better off financially” in a year, whether the next 12 months will be good times or bad times for “business conditions in the country” and whether the country will have “continuous good times during the next five years or so” or “periods of widespread unemployment and depression.”

Five years is a long time. Think back to 2018: Would you have done a good job answering what the next five years had in store?

This leads to an interesting observation about Michigan’s index from John Leer, the chief economist at Morning Consult, an online surveying firm. For the past five years, Morning Consult has asked the same questions about sentiment as the University of Michigan, but on a daily basis. Over time, their measures track quite closely.

But Leer notes that the daily index provides insight into what news events are causing sentiment to shift. In recent years, the news often had little to do with people’s direct economic experiences. Republicans became hugely pessimistic when Joe Biden was elected president. Democrats became hugely optimistic, a familiar partisan pattern.

Although the job market was fairly strong and inflation not yet surging in 2021, many people became˛ pessimistic as it became apparent that Covid-19 vaccines weren’t going to immediately extinguish the pandemic.

When you ask people whether they will be better off a year from now “you don’t see the political effects as much,” Leer said. But when you ask about widespread unemployment and depression over five years “that’s where there’s a lot of partisanship.”

Right now is a somewhat unusual moment, Leer said. The 2024 election isn’t yet front and center and moods right now don’t tell us much about how people will vote next November. The pandemic has faded. People really are thinking about the economy for once.

The Conference Board, by contrast, asks about business conditions in six months, job availability in six months and family income in six months.

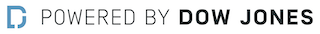

Despite a good current assessment, consumers have been incredibly pessimistic about this immediate future.

“In our measures, consumers are telling two different stories,” said Dana Peterson, chief economist at the Conference Board. “They’re saying, ‘Things are OK right now, but I think something bad is around the corner.’ ”

The views about the next six months, in fact, are so bad that they have typically signaled a recession, Peterson said.

The index was up last month, but not out of that recessionary danger zone, she added.

Confidence and sentiment might be slightly fuzzy concepts, and the questions used to measure them a bit fuzzy too. But they capture something genuine about the id of consumers. Despite the gauges’ different methods, they show people looking up, but also looking out for the other shoe to drop.

Write to Josh Zumbrun at josh.zumbrun@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.