By Tom Fairless

Sept. 19, 2022

FRANKFURT—Even as some prices such as for gasoline signal tentative easing of inflation pressure, the Federal Reserve and other central banks remain preoccupied with one that shows the opposite trend: the price of labor.

iStock image

Soaring pay growth, officials worry, could prompt businesses to keep raising prices to offset higher labor costs, producing a wage-price spiral.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey this year urged U.K. workers not to ask for big pay raises in an effort to cool inflation that is running at 9.9%, prompting criticism from labor unions. U.K. wages are currently rising by 5.5% a year, up from about 3.5% in 2019.

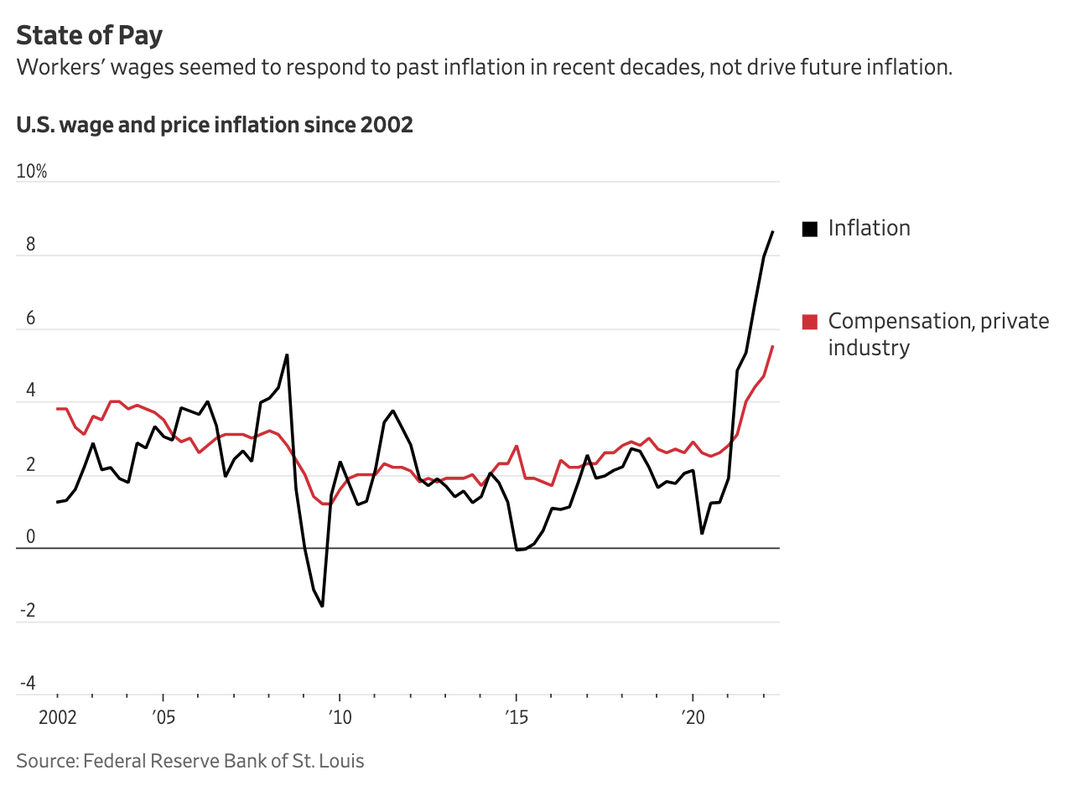

But some economists say the concern is misplaced. They say the lesson of the past few decades is that while higher prices lead to higher wages, as workers try to claw back lost purchasing power, the reverse isn’t true. If so, high wage growth won’t stand in the way of getting inflation down.

“I am concerned that this point may not be fully appreciated by some policy makers,” said Stefan Gerlach, chief economist at EFG Bank in Zurich. “Inflation and wages tend to move together, but that may be largely due to wages responding to past inflation, not inflation responding to past wages.”

Labor makes up the bulk of firms’ total costs in the U.S. and Europe. That means over time, rising wages should lead to higher prices, after adjusting for increases in workers’ output per hour. Otherwise workers would claim an ever-larger share of the economic pie at the expense of business owners.

In the U.S., hourly wages of private-sector workers were up 5.2% in August from a year earlier, a slower increase than 5.6% in July but much faster than around 3% before the pandemic. A different measure compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, which isn’t affected by shifts in jobs between high- and low-paying industries, put wage growth at 6.7% in July and August, the fastest in at least a quarter-century. Both, however, are lagging behind consumer prices, which rose 8.3% in the year through August.

In the eurozone, hourly labor costs climbed by 4% in the three months through June from a year earlier, and the European Central Bank this month announced a jumbo 0.75 percentage point interest-rate increase. ECB chief economist Philip Lane warned last week that faster wage growth contributed significantly to higher inflation.

State of PayWorkers' wages seemed to respond to past inflation in recent decades, not drive future inflation.U.S. wage and price inflation since 2002Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

But a variety of studies have found that over the past few decades, increases in labor costs haven’t been passed through fully or at all to prices.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found, in a 2020 paper, that U.S. manufacturing firms had largely stopped raising their prices in response to wage increases over the past two decades. Federal Reserve Board economists found little evidence in 2017 that changes in labor costs had a material effect on price inflation in recent years.

“The joint dynamics of inflation and compensation no longer manifest the type of wage—price spiral that was evident in earlier decades,” according to the 2017 paper.

In Europe, the pass-through of wage growth to core inflation (which excludes food and energy) declined by about one-third in the decade after the 2008 global financial crisis compared with the period before the crisis, according to a 2019 paper by International Monetary Fund economists.

The shift likely reflects growing international trade and rising market power of businesses since the turn of the century, as well as a general decline in inflation, according to research.

The argument goes like this: As foreign competitors moved in, some domestic firms shut down. The firms that survive have higher profit margins, making it possible for them to at least partially absorb higher wages without passing them to their customers and avoid losing market share to foreign competitors.

Crucially, though, inflation was generally low and stable in the period these papers examined. If businesses now expect wages and other costs to rise strongly and persistently, they might be less willing to absorb them. In Europe, some recent surveys suggest that consumers and investors expect inflation to remain high.

Research published last month by the New York Fed found that before the Covid-19 pandemic, for goods and services that are traded internationally, wage increases didn’t filter through to prices at all. That changed in 2021, when a 10% increase in wages was associated with a 1.4% rise in producer prices.

Some companies are citing higher labor costs for why they are raising prices. In February, Amazon.com Inc. Chief Financial Officer Brian Olsavsky cited rising wage costs as a reason behind an increase in the price of Prime membership in the U.S. to $14.99 from $12.99 a month—the first price increase since 2018. If pay growth is passing through more strongly to prices, wages and inflation could spiral upward together, requiring aggressive action by central banks to break the cycle.

The tight labor market represents an opportunity for workers to grab a bigger slice of the economic pie, after decades of globalization and weakened labor unions shifted leverage to business owners. If workers are successful, wages could rise strongly even as inflation slows.

Still, businesses retain considerable market clout at a time of strong demand, economists say, and are unlikely to give up their share of the pie without a fight.

Write to Tom Fairless at tom.fairless@wsj.com

Copyright 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.