Matthew C. Klein

July 17, 2019

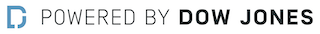

Futures prices currently imply a 100% chance the Federal Reserve will lower short-term interest rates from their current range of 2.25-2.5% at its next meeting on July 31. The only debate is whether the policy band will drop to 2.0%-2.25% or 1.75%-2.0%.

This marks a big change from November, when traders were overwhelmingly betting the Fed’s policy band would be at least 0.25 percentage point above its current range after this month’s meeting. As recently as March, market prices implied almost no chance of a rate reduction at the July meeting.

The Fed is unlikely to disappoint traders. Officials have made it clear their first priority is to “sustain the expansion,” and that this requires keeping financial markets on a reasonably even keel. Surprises—especially the kind that lead to higher borrowing costs and lower asset valuations—are not part of the program.

Some analysts think this is a recipe for a policy mistake. To them, the Fed is being dragooned into unnecessary interest-rate reductions by an unhealthy focus on market pricing. The alternative explanation is that traders and central bankers are both reacting to the same information about the underlying strength of the economy. If so, holding rates steady, much less raising them, could risk pushing the world into recession.

Michelle Meyer, head of U.S. economics at BofA Securities, recently compared Fed Chair Jerome Powell to a timid parent afraid of upsetting his tantrum-prone toddler. David Mericle, a senior U.S. economist at Goldman Sachs, warns that cutting rates in July could encourage traders to expect additional rate reductions and “create a positive feedback loop strong enough to trigger inappropriate policy moves” that would be difficult to undo without politically contentious rate increases on the eve of the 2020 elections.

These arguments are based on the theory that central bankers know better than traders. Mericle notes market prices have frequently implied policy changes that never occurred and that the Fed has rarely reversed itself after defying those expectations, which suggests that traders have “severely misjudged” what the Fed should do.

Yet Fed officials have also made mistakes, usually when they have stubbornly ignored market signals.

When short-term interest rates are higher than long-term interest rates, for example, traders are betting that shorter-term interest rates are going to fall and are willing to pay a premium to lock in longer-term yields. Since changes in short-term interest rates tend to track changes in economic conditions, the “inverted” yield curve has been a reliable predictor of downturns for decades.

Fed officials dismissed warning signals from the inverted U.S. yield curve in 1989, 2000, and 2006-07 for various technical reasons, yet each episode was followed by a recession. The Fed almost inverted the yield curve in 1995, but narrowly avoided doing so by lowering its policy rate by 0.75 percentage point and keeping growth going for another five years.

Most measures of the curve have been inverted for more than a month. Current pricing reflects the market’s reasonable belief that policy makers would prefer to repeat the experience of 1995 rather than 1989. Chris Waller, one of President Donald Trump’s latest nominees to the Federal Reserve Board, is a firm believer in the yield curve’s predictive power and associates inversions with “policy mistakes.”

Market signals are also useful for calibrating monetary policy. Central bankers need to have some sense of the “neutral” interest rate above which the central bank is holding back growth and below which the central bank is boosting the economy. Unfortunately, there is no reliable way to estimate this constantly changing number—which is affected by the saving and spending decisions of people all over the world—solely from traditional macro data.

Vice Chair Richard Clarida’s solution is to look at relative market prices. His preferred estimate of neutral has dropped by almost a full percentage point since November, which may explain why Fed officials have lowered their estimates of “appropriate monetary policy” by an equivalent amount over the past few months.

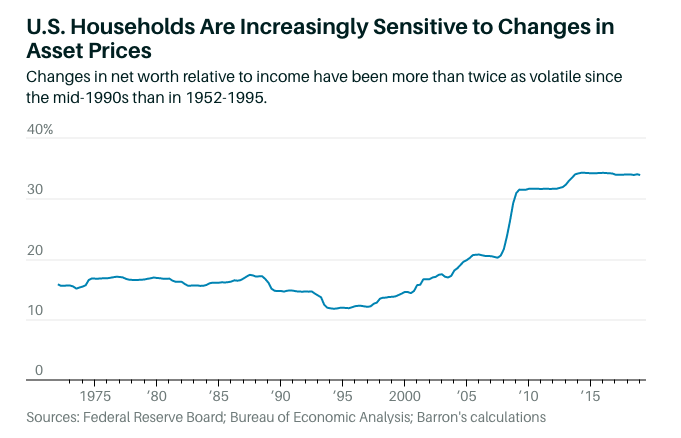

The Fed’s willingness to surprise or “discipline” markets may also be affected by the fact that American households have far more debt and far more risky assets than they did as recently as 30 years ago. Srinivas Thiruvadanthai, director of research at the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center, notes that changes in net worth have more than doubled relative to disposable incomes since the mid-1990s.

The drop in stock prices at the end of last year and the rebound at the beginning of this year drove two of the biggest quarterly swings in American net worth since the 1940s. The heightened sensitivity to changes in asset prices explains the surprising volatility of household spending at a time when “the job market is healthy,” Thiruvadanthai writes.

Whether or not central bankers want to defer to market expectations, they may not have much choice.

Write to Matthew C. Klein at matthew.klein@barrons.com

This Barron's article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream.

Copyright 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.