Greg Ip

March 9, 2023

Inflation rose sharply after the end of World War II as industry struggled to adapt to the shifts between military and civilian demand.PHOTO: ANTHONY POTTER COLLECTION/GETTY IMAGES

The economy has repeatedly flummoxed the experts in recent years. Almost no one expected inflation would rise so much, interest rates to jump so quickly, or higher interest rates to show so little effect on the economy.

So has something fundamentally changed about the economy? Yes, if the current economic cycle is compared with those of the 2000s. When the frame of reference is expanded to the last 80 years, the current cycle starts to make sense, though it’s no easier to predict.

Here are three ways this cycle is different from the recent past.

Supply, not just demand

Economic growth over many decades depends on the supply of goods and services made possible with labor, capital, technology and knowledge. But these factors change so gradually that economists largely ignore them when projecting near-term growth and inflation, focusing instead on demand: how much households, businesses, governments and foreigners want to spend. When demand is strong, growth and inflation pressure pick up. When it’s weak, they drop back.

Demand became even more dominant in economists’ thinking after the 2007-09 financial crisis when banks and households were reining in spending and borrowing to whittle down debt, keeping growth and inflation subdued despite near-zero interest rates.

But since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, supply has been as, if not more, important as demand in shaping the cycle. Lockdowns and reopening severely constrained numerous industries’ output, from shipping to automobiles. When firms that laid off employees went to hire them back, they found many had dropped out of the labor force because of Covid, child care, early retirement, reduced immigration and geographic displacement. The Fed last week put the labor shortfall relative to prepandemic estimates at up to 3.5 million in the fourth quarter.

Whereas reduced demand puts downward pressure on inflation, reduced supply does the opposite. That’s why wages and prices rose much faster after the pandemic than after previous recessions, which were demand-driven.

The pandemic brought “a bunch of firsts,” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell told Congress on Wednesday. “Nobody had seen supply chains collapse, labor-force participation plummet.”

They weren’t really firsts. A loss of oil supply contributed to inflation and recession in 1973 and 1980. Inflation rose sharply after the end of World War II in 1945 and the start of the Korean War in 1950 as industry struggled to adapt to the shifts between military and civilian demand.

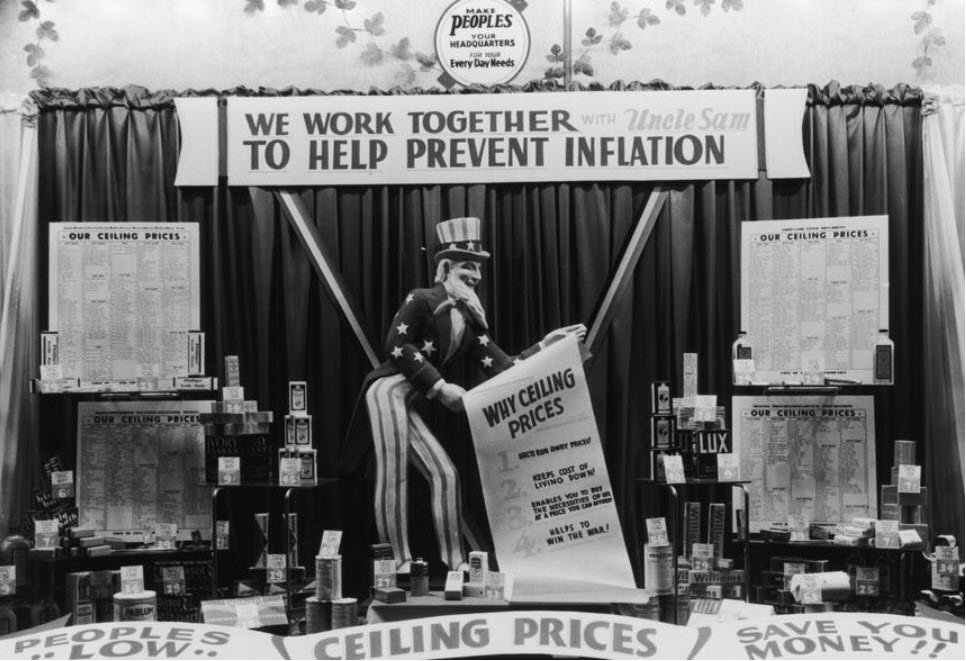

Just as a fall in supply pushes inflation up, recovering supply pushes it down. This is already apparent in the prices of durable goods which have been dropping since August. Typically, when job vacancies fall, unemployment rises, because both reflect falling demand for labor. But in January, vacancies and unemployment both fell, a sign of an increased supply of labor—corroborated by company reports that worker shortages are less severe. Women who left work because of child care responsibilities have mostly returned, and immigration is now bouncing back.

In a recent report TS Lombard economist Dario Perkins noted the same thing happened from 1946 to 1947: vacancies fell sharply without any increase in unemployment. “Post-WW2 labor demand was satiated by an increase in labor supply, as soldiers returned from the war and re-skilled,” he wrote. This, he said, is the best template for how the Fed might achieve a “soft landing” rather than a recession this year.

Inflation is too high, not just right

Democratic legislators this week asked Mr. Powell why the Fed was still raising rates when its officials’ own forecasts project unemployment rising to 4.6% from 3.4% this year, a magnitude usually seen only in recession. “To prevent a recession, yes or no, Chairman Powell, will you pause future interest rate hikes?” Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D., Mass.) asked.

Ms. Pressley’s question, which Mr. Powell declined to answer, was understandable given that in the previous 25 years, the Fed not only stopped raising rates but cut them when unemployment rose.

But throughout that time, inflation fluctuated in the 1% to 3% range. This meant there was no need for the Fed to push unemployment higher to get inflation down to its target, formally set at 2% in 2012. This left the impression there was no trade-off between unemployment and inflation. Quite the opposite: The Fed felt free to focus more attention on unemployment.

But the trade-off never went away, it just wasn’t as relevant when inflation was so well behaved. In previous eras the trade-off was very much evident. In 1973 and 1981, the Fed induced recessions to get inflation lower.

It is in that situation again today. Depending on the index, inflation is now running at 4% to 5% excluding food and energy. Improved supply may bring it down somewhat, but to get it to 2%, the Fed thinks demand has to fall as well, which means higher unemployment. Strong economic news is therefore bad news because it means the Fed has more work to do.

No financial bust means no recession, yet

Despite the steepest interest rate increases since the 1980s, the most anticipated recession in history has yet to materialize.

That’s because the impact of rates depends crucially on how they are transmitted more broadly. In the 1990s and 2000s, financial innovation, deregulation and globalization made the financial system fragile and prone to asset booms and busts. When the Fed tightened monetary policy in 1999-2000, it deflated a bubble in tech, media and telecommunications stocks and bonds, which then dragged down business investment and hiring. When it tightened in 2004-06, it deflated a housing bubble, which then triggered a wave of mortgage defaults and a devastating financial crisis.

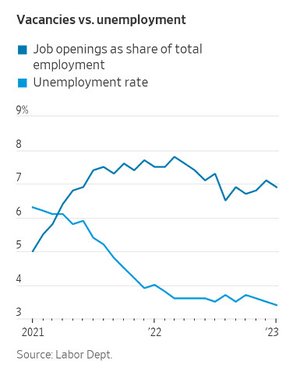

Nothing like that has happened yet. A measure of financial stress developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, which shot up in previous recessions, is flat. The deleveraging and reregulation that followed the financial crisis has made lenders more conservative and less vulnerable. Stock and property valuations haven’t gotten as extreme as in 2000 or 2006. Households and businesses have relatively strong balance sheets, in part thanks to pandemic-era stimulus.

True, cryptocurrencies have collapsed, taking down unregulated platforms such as FTX and, this week, Silvergate Capital, a bank catering to crypto. But these are relatively tiny operations with few linkages to the rest of the economy and financial system.

Of course, there may be time bombs buried in the financial system still waiting to go off. But until they do, the Fed will have to rely on interest rates alone to accomplish its job.

Copyright Dow Jones and Company 2023