EVAN ANNETT

Nov. 1, 2020

If all goes well, Americans will elect their next president on Nov. 3. Except they’re not technically electing him, and the people who are won’t be doing so for another few weeks. If all goes well, that is.

Confused? Welcome to the U.S. electoral system. Since the 18th century, Americans have chosen their presidents through a small and little-understood group, the Electoral College, and a formula that uses states' voting results to tell its members what to do. Even in normal times, U.S. elections can be a messy process, but in a Trump-era pandemic there are extra challenges at every step: Long lineups at polling stations could delay their closing times, the counting of mail-in ballots could take days or weeks and, in the chaos, the President could claim victory prematurely or refuse to accept defeat.

Here’s an overview of how the Electoral College works and why it exists, so you know what to expect on election night and the weeks afterward.

How the Electoral College works

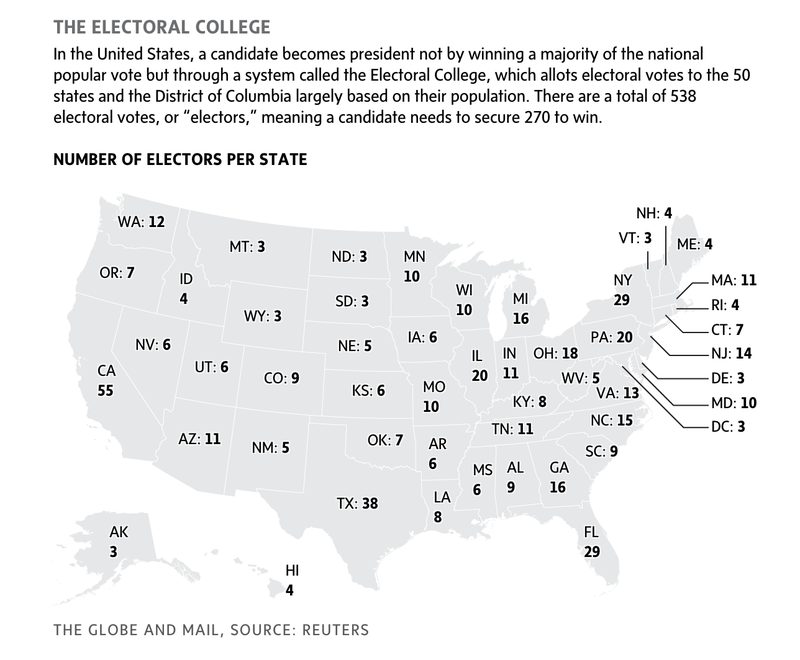

The popular vote doesn’t automatically decide who becomes president, as Hillary Clinton learned in 2016 when she outperformed Donald Trump but still lost. The decision is actually made by 538 people called electors, who vote in mid-December based on how their states' results turned out. All but two states are winner-take-all: If, say, 51 per cent of Floridians vote for Joe Biden, he gets all 29 of Florida’s Electoral College votes. The exceptions are Maine and Nebraska, where it’s a mix of statewide popular vote and results by congressional district. Whichever candidate gets 270 votes or more is elected president.

WHY DO SOME STATES HAVE SO MANY MORE VOTES THAN OTHERS?

The Constitution gives each state a certain number of seats in the House of Representatives based on their populations, as measured in the census every 10 years. Then, states get that number of votes plus two in the Electoral College. (The District of Columbia, while not a state, gets three college votes, but there are none for U.S. overseas territories like Puerto Rico or Guam.)

Big states get a lot of votes in absolute terms, though not in terms of votes per capita. The most powerful voters are actually in states such as North Dakota and Wyoming, because no matter how small they are (Wyoming has fewer people than the city of Hamilton), they can have no fewer than three college votes. So their voters have disproportionate power, while those in big states such as New York and California are underrepresented.

WHO ARE THE ELECTORS?

Sometimes they’re regular people such as teachers or firefighters who are registered members of a party, but they may also be party functionaries or politicians: In 2016, Bill Clinton was an elector in New York state, and voted as instructed for his wife. Each state party has its own methods for picking slates of electors, and whichever party wins the state sends them to the Electoral College. The final lists of electors may not be complete until December: By federal law, states have until Dec. 8 to settle any disputes about their slates.

DO ELECTORS HAVE TO VOTE FOR THE PERSON THEIR STATE CHOSE?

No. A few, called unpledged electors, are allowed to support anyone they want. Even pledged electors can break their promise, in which case they’re called faithless electors: These are rare, but there was a record number of them in the last election – seven people who succeeded in casting what were essentially protest votes against their assigned candidate. Some states have laws that say faithless votes shouldn’t be counted, but there’s nothing in the U.S. Constitution to stop faithless electing in general.

WHAT HAPPENS IF THERE’S A TIE?

If neither Mr. Trump nor Mr. Biden can reach 270 votes, then it’s up to the newly elected House of Representatives to solve the deadlock in early January with what’s called a contingent election. This wouldn’t be like a normal House vote, where a simple majority wins: Here, each state’s delegation of legislators decides as a bloc who should be president, and the candidate who gets 26 states or more wins. The presidency hasn’t been decided in this way since 1825: After a general election with four candidates, three made it to a contingent election where lawmakers chose John Quincy Adams instead of Andrew Jackson, even though Jackson had received more college votes than Adams. (Jackson would defeat Adams in the next election, and today Mr. Trump is an outspoken fan of his.)

Why do Americans choose their president like this?

When the framers of the U.S. Constitution got together in 1787, few expected they would agree to a one-person presidency at all, and few agreed how they should elect such a person. Straight popular elections were considered, but rejected, for three main reasons:

- Self-interest: The founding states saw themselves as sovereign, and while they agreed a stronger central government was needed, they still wanted an executive that was in some way answerable to all of them. They feared a directly elected leader would answer only to the most populous states, or abuse their mandate for autocratic ends.

- Racism: Agrarian slave-owning states, whose Black inhabitants couldn’t vote, feared direct presidential elections would give white southerners less influence than the mostly free populations of other states. This fear also shaped the way the Constitution calculated the makeup of the House, and by extension the Electoral College; Enslaved Black people counted toward states' seat numbers, though for this purpose they were considered only three-fifths of a person. (Even after slavery was abolished, anti-Black voter suppression tactics allowed white people to keep much of this influence on Electoral College outcomes. And the formula still hampers Black voters today because the states with low per-person voting power also tend to have the biggest Black populations.)

- Logistics: Eighteenth-century America was a pre-industrial world in which people and information travelled slowly. The Founding Fathers couldn’t have imagined an orderly, timely election on a nationwide scale, especially in an era where voting was done by groups of people stating their decisions in public, not by secret ballot.

The framers' original solution to these problems was to have Congress pick the president, but then they worried lawmakers would be too easily manipulated by political parties, which were not yet well-established in the new republic. The framers concluded that a small group of ordinary people would be less corruptible and free from the “heats and ferments” of public opinion, almost like citizens on jury duty. As a further safeguard, the Constitution forbade all the country’s electors from meeting in the same place at once, which is why each state’s electors meet separately. But over time, electors became beholden to party interests anyway because Democrats and Republicans took charge of selecting them.

Which states could decide the outcome?

The process we’ve just described may sound complicated, but for Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden, the goal in any given state is a simple one: Win the biggest popular vote and take the Electoral College votes. That’s easier said than done in places where polling suggests the results will be close, and where support has alternated between Republicans and Democrats in the past (sometimes called purple states).

Depending on whom you ask, there are seven to a dozen states that could be considered battlegrounds, including Pennsylvania, Florida, Arizona, Wisconsin, North Carolina and Ohio. In the interactive Associated Press map below, you can explore different scenarios for how the battleground states might swing, based on the outcomes of past elections.

This Globe and Mail article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream.

© Copyright 2025 The Globe and Mail Inc. All rights reserved.