By Spencer Jakab

March 17, 2023

The opening shot in “Animal House” pans across the campus of idyllic Faber College, focusing on a statue of its founder inscribed with the words “KNOWLEDGE IS GOOD.”

The statement is so obvious as to be laughable—the perfect way to kick off an hour and 49 minutes of not-so-subtle humor. But is knowing more always good? In investing at least, it isn’t. It could even hurt.

ROBERT NEUBECKER

Wall Street traders surround themselves with screens crammed with blinking numbers and charts—four are now par for the course, but six or even eight have become common. And fund managers can consult thousands of Wall Street analysts for their forecasts and opinions before buying a stock. At least 30 follow Apple. Many also employ in-house analysts and rent Bloomberg terminals for $30,000 a year.

Retail investors used to rely on daily stock listings with a few basic ratios like dividend yields or on newspaper articles like this one. Now they have narrowed the information gap tremendously with access to armies of amateur analysts through services like SeekingAlpha and data feeds resembling those pricey terminals.

A fascinating experiment explains why both pros and amateurs probably should save their money. In 1973 psychologist Paul Slovic gathered eight talented handicappers to guess the outcome of 40 actual horse races in four rounds. The names of the jockeys and steeds were hidden, but the handicappers could ask for five pieces of information from a set list of 88. They were also asked to say how confident they felt. The handicappers did well, reaching 17% accuracy compared with 10% if they had guessed blindly. Their confidence was almost exactly right too at 19%. In the next three rounds they could ask for 10, 20 and finally 40 bits of information and their level of conviction rose steadily, reaching 34%. But their accuracy? It stayed at 17%.

At least knowing more didn’t do any harm. At a real horse track, though, or in the stock market, detailed knowledge emboldens people to make riskier bets. And, since most people aren’t experts at either horses or stocks, reports making confident predictions filled with complicated calculations or claiming inside knowledge can override the common sense of pros and amateurs alike.

In October 2001, with suspicions swirling, five Goldman Sachs analysts wrote an 11-page report calling Enron “still the best of the best” after they had extensive conversations with top management: “our confidence level is high.” The stock rallied by as much as 8% over the next two trading sessions, but Enron would file for America’s largest-ever bankruptcy within weeks.

The lessons of that meltdown didn’t exactly endure. When millions of young investors opened their first brokerage accounts during the pandemic’s first year, many took cues from “finfluencers” who spoke their language or from peers using pseudonyms. Social-media site Reddit has a forum with more than half a million members following a single company, AMC Entertainment Holdings. The problem with crowdsourcing research on social media is that people mainly find evidence that supports their existing thesis. Psychologists call this confirmation bias.

“Ideally, you find a tribe that’s encouraging you to look at the other side,” says Rishi Khanna, chief executive of StockTwits, one of the earliest and largest investing-focused social networks, with around seven million users. He says the bias is overwhelmingly bullish. Official Wall Street is hardly more balanced. A report by FactSet last April showed that, of 10,821 analyst ratings on stocks in the S&P 500, fewer than 6% were sell recommendations.

Bad takes abound, but legitimately valuable knowledge can overwhelm users too. Leigh Drogen founded a firm called Estimize that queries pros and amateurs on things like earnings estimates. Its polls are more accurate than the consensus of stock analysts, but not always. He says that snapping up every bit of data and expecting it to work consistently often tripped up his clients.

“Paying attention to five things in a highly efficient, systematic way will always beat paying attention to 50 in an undisciplined way,” he says.

The fire hose of information available to retail investors through their smartphones is even worse. When millennial-focused broker Robinhood sold shares to the public in 2021, it revealed that active customers checked the app more than seven times a day on average. The knowledge they gleaned from looking so frequently was almost certainly detrimental.

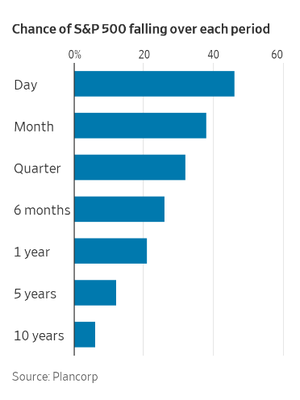

One reason is a phenomenon called myopic loss aversion. The more often one looks at a financial account the more likely one is to see a loss and, since losses bother us more than gains, they spur turnover. Investors who trade the least often make the most, and vice versa, even after adjusting for trading costs, according to a landmark study “Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth” by professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean.

The explosion of financial data and the ease of instantly trading on it also creates more mistakes, though occasionally they are pleasant ones. Some investors made fortunes accidentally buying Sysco, the restaurant-supply giant, instead of Cisco Systems, the computer-networking company, for example, or an all-but-defunct company called Zoom Technologies when they meant to invest in work-from-home standby Zoom Video Communications. More recently, meme stocks have surged after bad message board analysis went viral.

Just like Bluto’s motivational speech in “Animal House” about the Germans bombing Pearl Harbor, the trick is riding the craziness and then getting out of town in time.

Write to Spencer Jakab at Spencer.Jakab@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.