Amy Borrett

Aug. 28, 2023

Employers are starting to look more at skills than education, which is good news for students opting not to go to university.

Eden Heath has a clutch of top grades in her A-levels and was head girl at the south-east London school where she just finished her final year. University would seem a no-brainer for her. But like many of her friends, she thinks it is a waste of money and only plans to go as a last resort.

“University has become a back-up option for a lot of people,” she said. “Apprenticeships are a massive thing, especially in my year group . . . You come out with no debt and more experience — and you’re getting paid.”

For decades university degrees have been a must-have for entry-level professional roles. But there are signs this is changing, as students consider other ways of acquiring skills and employers offer new paths to competitive careers.

In the UK, the Institute of Student Employers (ISE) found the share of members requiring a 2:1 degree fell from three-quarters in 2014 to less than half in 2022. A separate analysis by website Totaljobs found just 22 per cent of UK entry-level adverts mentioned a degree this year, a decline of almost a third since 2019. Job postings that did not require a degree increased 90 per cent between 2021 and last year, according to LinkedIn.

Employers as varied as the cereal maker Kellogg’s UK and the state government of Utah have stopped requiring degree-level qualifications. Companies including IBM and Accenture, meanwhile, have invested in hiring routes such as apprenticeships so new recruits can train on the job.

Management professor Joseph Fuller, who co-leads Harvard Business School’s Managing the Future of Work programme, applauded companies widening recruitment beyond graduates. But he cautioned this was only a first step that would not change the behaviour of hiring managers.

“The fact is that for a lot of companies it’s just virtue signalling,” he said. “But I think eliminating degree requirements is smart business and an appropriate thing to do.”

Has the value of university declined?

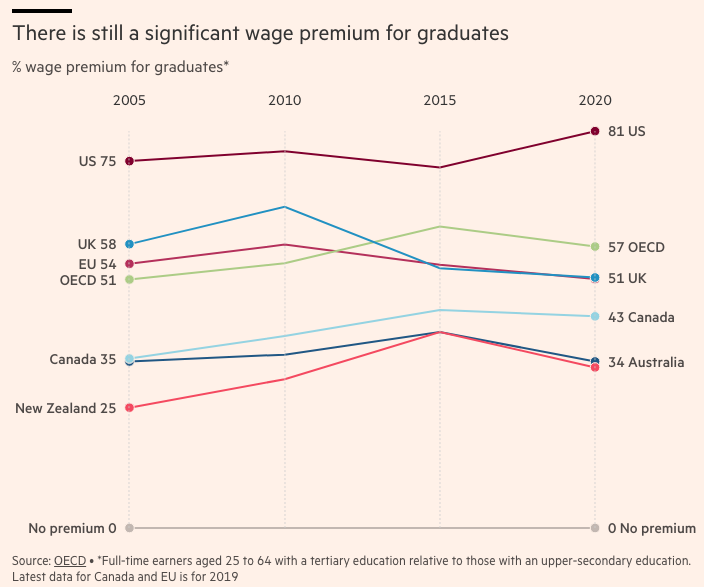

Recruitment may be shifting away from universities but companies continue to pay a premium for graduates.

In the US, this “graduate premium” — the wage boost received by people with a degree — increased from 75 per cent to 81 per cent between 2005 and 2020, according to a Financial Times analysis of figures from the OECD group of rich nations. In the EU and UK, graduates are still paid about 50 per cent more than people without a degree.

This is despite an increase in the number of graduates, which could potentially dilute a degree’s value on the jobs market. In the US, 51 per cent of 25 to 34-year-olds were college graduates in 2021, compared with 38 per cent in 2000; in the UK, 57 per cent of young adults were university educated in 2021, up from 29 per cent two decades ago.

Stephen Isherwood, ISE chief executive, said the graduate premium had held up because jobs had become more complex, and roles requiring degree-level skills had increased with the number of graduates.

“To be a nurse, to deal with technology and to deliver different kinds of medicines requires degree-level education,” he said. “The same is true for other roles like internal finance.”

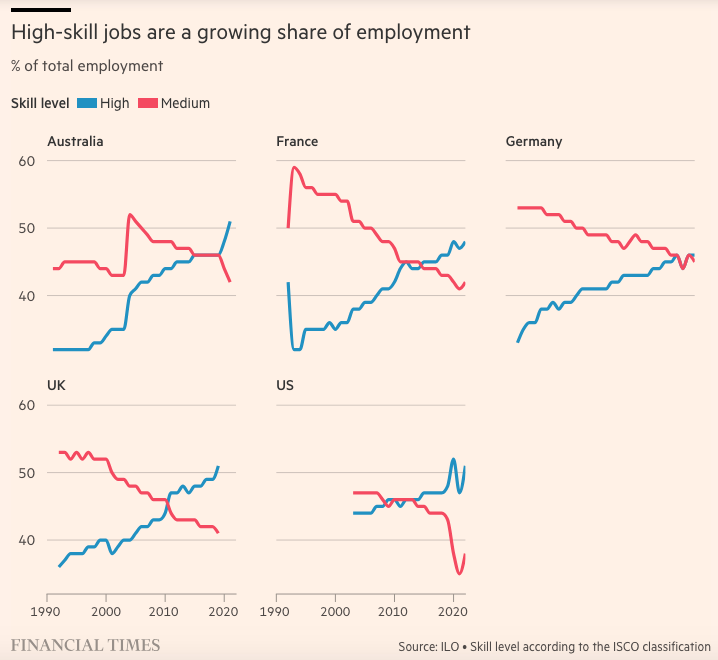

The proportion of high-skilled roles, which involve complex tasks and require high levels of education or training, have grown in developed economies for more than three decades, according to the International Labour Organization.

Wenchao Jin, assistant professor at the University of Sussex, said the rising number of high-skilled jobs had itself been driven by more people having degrees. “The occupational structure has really adapted to absorb all these extra graduates as educational attainment shifted.”

Hiring for skills, not education

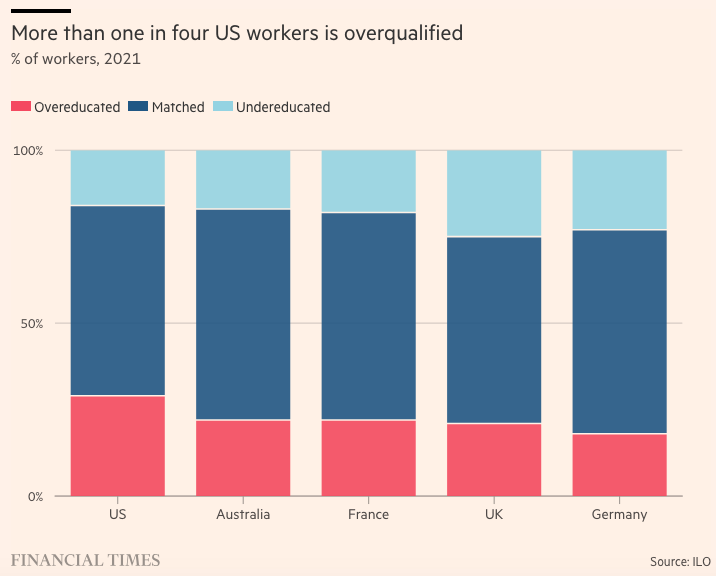

Despite the increase in high-skilled work, almost a third of workers in the US and more than a fifth in some big European economies are overeducated for their job, according to the ILO. Many graduates are stuck doing jobs that could be done by non-graduates.

This can in part be attributed to employers advertising lower skilled roles as requiring a degree — even if they do not in reality.

In the US, for example, two-thirds of production supervisor roles asked for a college degree in 2015, despite only 16 per cent of people already in the role having one, according to a Harvard Business School study. It found this resulted in posts being harder to fill, higher staff turnover rates, and more expensive hires, leading to worse outcomes for companies.

The fear of being unable to find a role that matches her qualifications is one reason Heath hopes to opt for a digital marketing apprenticeship over university. With annual tuition fees of more than £9,000, which are repaid through salary deductions over her working life, cost is another.

“It scares me so much,” she said. “If I did a degree and I came back and nobody was interested in hiring me, then I’d have wasted four years and all that money.”

This reflects a broader shift. Less than half of Britons think it is worthwhile for a young person to do a degree, according to a study this May by the pollsters Ipsos.

Targeting non-graduates

In some countries, policy decisions have driven non-graduate recruitment.

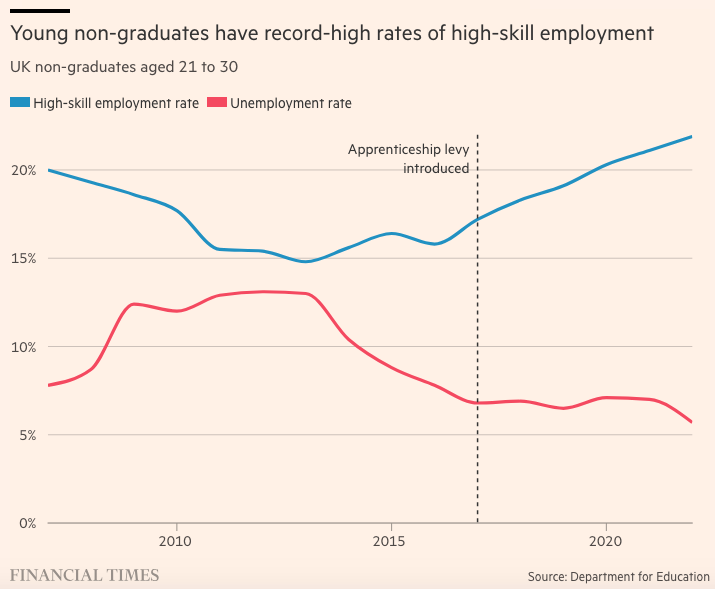

The UK’s apprenticeship levy requires employers to spend a proportion of their payroll on training. Since it was introduced in 2017 rates of high-skill employment for non-graduates have risen almost five percentage points.

IBM started hiring apprentices in 2010 as part of a wider expansion of non-graduate recruitment. Degrees are required for just 12 per cent of advertised UK positions and less than half of those in the US, the company said.

Jenny Taylor, IBM’s early professional programme lead, said it initially seemed a “bit of a risk” to hire 18-year-olds in client-facing roles. But recruits “have proved to us time and time again that they can do it right from the start.”

By their early twenties, apprentices already had several years on-the-job training, she added, putting them ahead of graduate hires. They also have the best training ground to develop “deeper” technical skills, such as artificial intelligence and quantum.

Some companies regard non-graduates as vital to inclusion efforts. Penguin Random House UK, for example, dropped degree requirements in 2016 and said its workforce had diversified as a result.

“We wanted to remove barriers that were precluding people with the skills and potential to succeed,” Claire Thomas, director of organisational development at the company, said.

Skills for the future

Rapidly changing demand for skills could also boost the need for degrees.

Almost a quarter of jobs will be disrupted in the next five years, according to employers surveyed by the World Economic Forum. Lower-skilled roles are most at risk, but it expected transferable skills such as creative and analytical thinking to increase in importance.

These, and other skills such as social intelligence or complex problem solving, are all honed by university education, said Fuller, the Harvard professor.

In a report released this month, Universities UK, which represents higher education institutions, projected that 88 per cent of new jobs would be graduate level by 2035. Universities, it said, “play a huge role not only in preparing graduates for employment, but also in teaching them crucial, transferable life skills” and growing the economy.

However, Fuller added that new technologies such as artificial intelligence could also be a “level setter”, helping non-graduates to overcome deficits in skills such as writing, where they have historically underperformed.

They could also enable employers to screen candidates in more varied ways, reducing the reliance on degrees.

“It’s very hard for employers to qualify workers, which is why they often default to proxies like a college degree,” said Fuller.

“Technology may open more opportunities for non-college graduates, as it will address the difficulty of understanding what someone’s done and its relevance.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2024

© 2024 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.

This article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream