By Paul J. Davies

Sept. 2, 2019

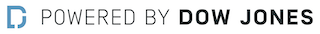

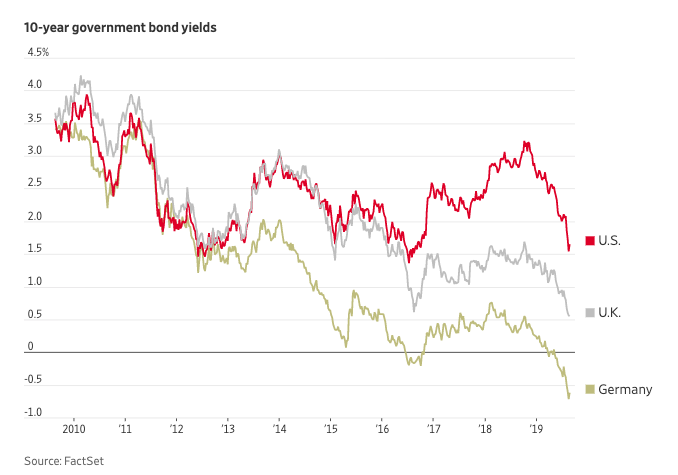

Long-term bonds have been on a tear in recent weeks with yields tumbling enough to heighten fears of a possible recession ahead.

But the bond market’s closely watched signals may have become exaggerated.

That is because part of the recent fall in bond yields—which drives bond prices higher—has been caused by banks, insurers and other investors essentially buying on autopilot, scooping up more bonds because that’s what their pre-existing risk models and investment-hedging strategies tell them to do.

“There was a fundamental driver to this move in yields and that continues to be validated by economic data and the Fed,” said Josh Younger, head of U.S. interest rates derivatives strategy at JPMorgan in New York.

“But the signals provided by the rates markets are being amplified by this hedging activity.”

The strong rally in long bonds such as the 10-year U.S. Treasury note and the 30-year bond has made them among the best performing assets of any market in the world this year.

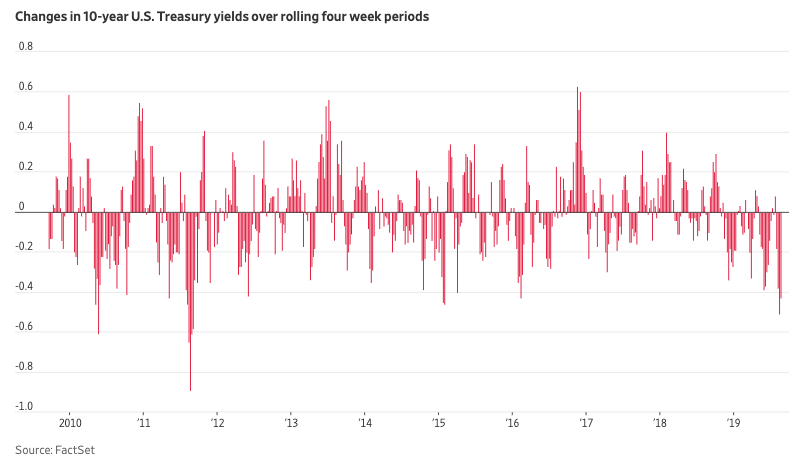

They also caused dreaded inversions of the U.S. yield curve in August, most notably one where the 10-year yield falls below the two-year yield, a warning that a recession may be around the corner.

Still, less than half the fall in 10-year yields during August—the biggest monthly drop in percentage point terms since 2011—came down to economic reasons, according to Mr. Younger.

He figures the recent 10-year Treasury yield of 1.5% is about 0.25 percentage point below where it would be without hedging activity, sometimes called “forced buying.”

One giveaway that the hedging activity has been important in recent market moves is that yields in a part of the derivatives market where hedging is done have fallen faster than those on bonds, according to Mr. Younger.

Here’s how one prominent hedge works for bond investors. Falling rates lead to a wave of Americans refinancing home loans. That means mortgage-backed bonds get paid off quicker than expected.

Institutions who owned those mortgage bonds—banks, mortgage real-estate investment trusts and fund managers, for example—are then pushed into buying longer-dated Treasurys or interest-rate swaps as the quickest and cheapest way to replace the income that disappeared with the now paid-off mortgage-backed bond.

Buying also comes from pension funds and insurers that sell annuities.

When yields fall, their liabilities often grow faster than their assets. That can increase the shortfall between what they are going to earn on their assets and what they owe to pensioners, also known as the “duration gap.” To close the gap, these businesses need more long-term assets such as longer-dated Treasurys.

Bets on low volatility in the bond options and futures markets—a trade popular among more flexible, or “unconstrained,” bond funds—can also produce demand for long dated bonds when volatility spikes.

These trades rely on volatility and yields remaining within a limited range. When yields break lower, as they have recently, investors need to rebuild their long-term exposure quickly and rush into government bonds or related swap markets to do so, says James McAlevey, head of rates at Aviva Investors in London.

On Wall Street, these effects all have typically obscure sounding names: mortgage bond owners face “negative convexity,” the risk that the duration of portfolios, or the time it takes for an investor to be paid back through coupon payments, could grow or shrink rapidly.

Those betting on low volatility can find themselves “short gamma,” which refers to the risk of market losses on short-dated options on longer-term bonds and interest rate swaps.

“The lower we go in long-term bond yields, the more demand starts to increase for certain products: gamma hedging, convexity hedging and closing duration gaps,” said Mr. McAlevey. “You end up with a market that is all buyers and no sellers.”

None of these activities kick off a market move, but they can help it gather pace, said Mr. McAlevey. Hedging activity linked to volatility strategies can also create forced sellers when yields start to rise.

“Gamma hedging works both ways,” he said. “A lot of what’s going on is just going to lead to higher volatility.”

The upshot is that without these flows, the U.S. yield curve wouldn’t have inverted and there would be much less fevered chatter about a coming recession.

“The flattening of the [yield] curves has been exacerbated by these flows,” said Stefano Di Domizio, head of fixed-income strategy at Absolute Strategy Research.

To be sure, all this hedging activity might have helped yields in the U.S. and Europe to fall more quickly to a level where they will eventually deserve to be.

In “the middle of August, it’s quiet, so moves get exaggerated,” says Helen Anthony, a portfolio manager at Janus Henderson. “We were expecting this to play out over much longer than just” August.

Write to Paul J. Davies at paul.davies@wsj.com

Copyright 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.