Constance Sommer

Sept. 11, 2023

Tara Driver would love to retire before age 70. But it’s not going to be easy.

The 51-year-old’s finances are still recovering from the hit they took more than a decade ago, after she spent about eight years caring for her ailing father.

During that time, every extra dollar went to pay for supplies and care for him, a veteran who died after a series of strokes and other complications. When she lost her job as an academic adviser because her employer shut down, Ms. Driver had to pull money she’d amassed in a 401(k) from two jobs before, as a program manager for the Y.M.C.A., so she and her father could survive until she found more work. She also deferred payments on her student loans, forced to let the interest build up.

Miriam Martincic

Under a federal law enacted 30 years ago, the Family and Medical Leave Act, the majority of American workers can take up to 12 weeks off work each year to care for a family member without fear of losing their job. But that leave isn’t paid. So some states are taking on the issue.

This year, Minnesota and Maine became the latest of 13 states, along with the District of Columbia, to offer paid caregiving leave. The programs cover all eligible workers and are financed either by workers alone, or workers and employers. Lawmakers have also recently introduced bills in Illinois, Michigan and Pennsylvania, among others.

“We’ve seen tremendous momentum and progress in the states,” said Dawn Huckelbridge, the director of Paid Leave for All, an advocacy organization. “Just in the last year, it’s incredible to see what’s happened.”

If she’d had paid leave, Ms. Driver said, she is sure she could have helped her father stay healthier longer. At the very least, she wouldn’t have had to take time off without pay just so he could go to an appointment. “I could have continued to maintain financially,” said Ms. Driver, who now works at Women Employed, a Chicago nonprofit, running programs that help women of color advance in the workplace.

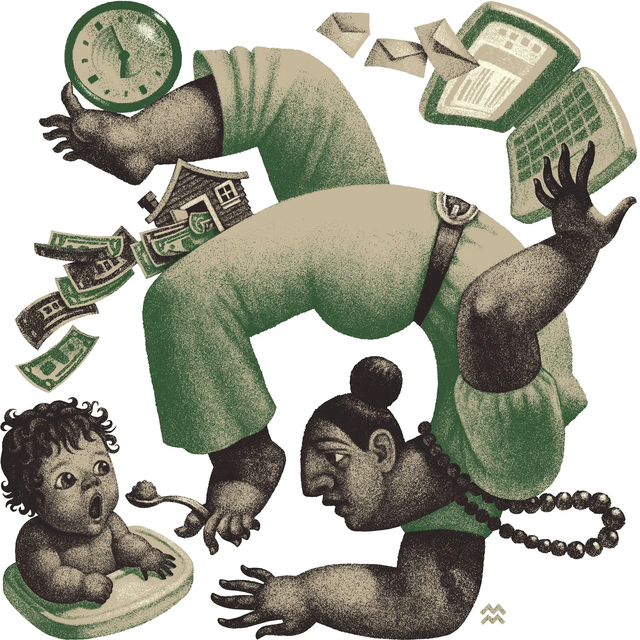

When a family member or close friend falls ill, many Americans face a predicament: Can they provide adequate care for their loved ones while earning enough money to pay their own bills? It’s a juggle even with paid family leave laws, which still cover fewer than a third of U.S. workers.

A 2018 report by the World Policy Analysis Center found that replacing at least 80 percent of a person’s wages was necessary to keep families out of poverty, and to help middle-class families continue to meet essential needs, like paying their rent or mortgage. New York and Rhode Island offer less than 70 percent wage replacement, while other states reduce reimbursements for people with higher incomes. In Colorado, for example, where paid leave begins next January, reimbursement for those earning at or below $710.58 a week is 90 percent. Reimbursement is 50 percent for those earning more than that wage, up to a weekly maximum of $1,100.

Paid family leave “is not a silver bullet,” said Jason Resendez, the president and chief executive of the National Alliance for Caregiving, a nonprofit advocacy group, “but it is one of the additional missing elements in the toolbox to help families better balance caring work and stay in the work force and provide economically for their families.”

Leave programs, however, can drag workers and employers alike into a sticky web of government red tape and regulation, said Rachel Greszler, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative public policy organization. In Washington, D.C., for example, where her husband works, some employers forbid their employees from even answering an email when they are taking paid family leave, so they don’t violate the district’s strict rules, she said. And the nation’s patchwork quilt of state policies means large employers can find themselves parsing contradictory policies across state lines, she said.

“Employers are probably best able to provide flexible and accommodating policies,” she said. “And they’re best able to do that if there’s not all these rules and regulations placed on them.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company