John Authers

Nov. 6, 2023

Tipping Point?

What just happened? Last week was a busy one for macroeconomic announcements. The essential points to emerge from it are as follows:

- The US Treasury cut back slightly on the amount of long-term bonds it’s planning to auction, compared to prior plans;

- The Bank of Japan allowed 10-year yields to rise, but didn’t release control completely, as some thought possible;

- The Federal Reserve offered guidance taken as a strong hint that it didn’t plan any more rate hikes;

- US unemployment data were both weaker than for the month before, and weaker than expected.

The first three make clear that global authorities aren’t necessarily prepared to let bond yields run riot — a notion that had gained strength since Jerome Powell’s interview with David Westin of Bloomberg TV last month, where he said that yields would “play out” and that he wasn’t “blessing” any particular level. This matters. Central bankers and finance ministers aren’t madly driving the economy or the financial system until something crashes, and don’t want to take the risk of a disorderly surge in bond yields.

US consumer spending will be tested in coming months. Photographer: Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg

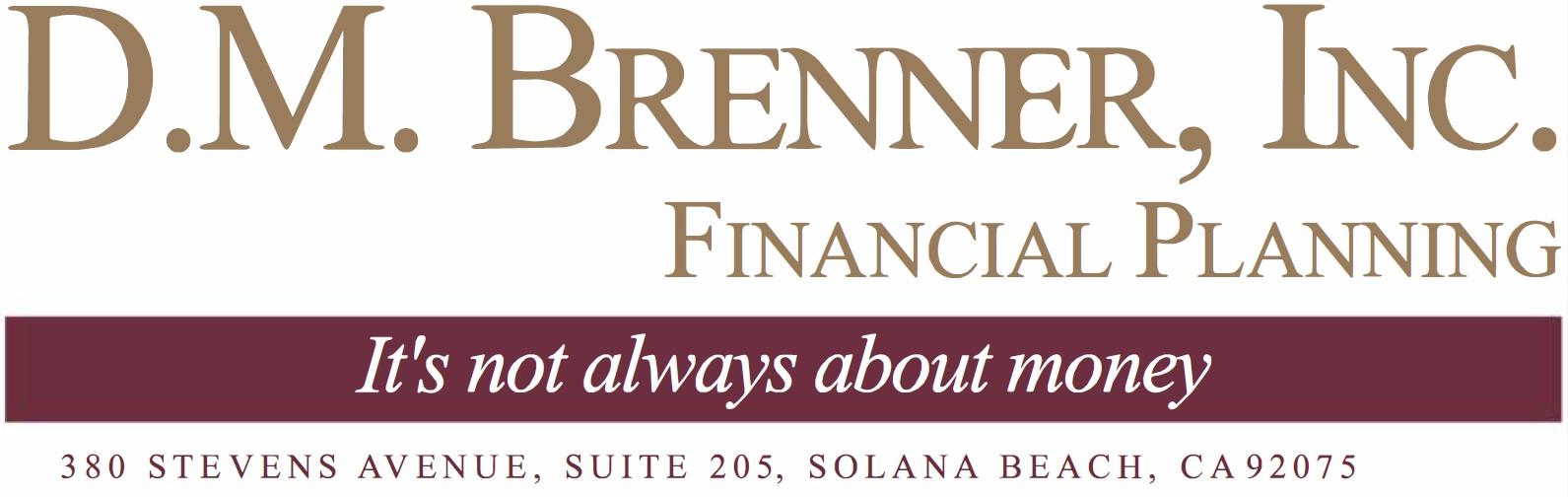

The fourth suggests that the direction of US labor markets is weakening, which in turn implies that it will be easier to bring inflation down. Rising unemployment could yet force interest rates down fast, as it has done several times in the past.

A change in direction at the margin matters for the economy and for markets. It always does. But we need to keep this in context. The unemployment rate rose to 3.9%. That’s its highest since January of last year. But in historic terms, it’s not very high at all and there could be much further to go. In this chart, I’ve excluded the months when the unemployment rate was most distorted by the pandemic, for legibility:

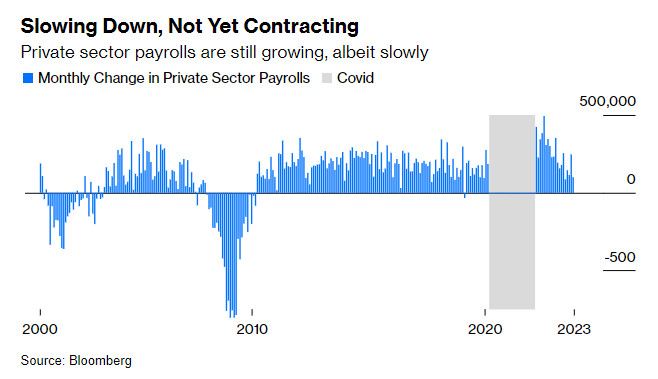

Private sector payrolls are still growing at a normal rate. The rate of change matters, and it shows deceleration, but companies are still expanding their workforce:

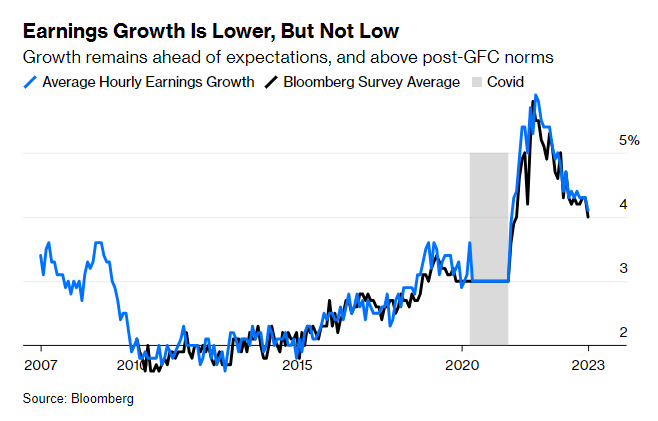

Meanwhile, the single most important aspect of labor growth as it affects inflation, wage growth, came in slightly above expectation. Average hourly earnings are now rising at 4.1% per year, which is a great salve for the stagnation in the years after the Global Financial Crisis. The strength of recent industrial actions, led by what appears to be a very generous deal won by the United Auto Workers, suggests that labor’s bargaining power is still in the ascendant, at least for now. So it’s hard to see this measure as being particularly positive for markets, although again, to be clear, it is trending in the direction that most investors want to see:

All this said, how exactly has the market reacted? This is where it gets very interesting. After a summer in which the Fed and other central banks had convinced markets that they really would keep rates “higher for longer,” that belief has taken a sharp knock. Bloomberg’s estimates of the rates priced in for the Fed in January of 2025, and for the European Central Bank in June next year, have dropped very sharply. The assumption once more is that the easing cycle will get going next year and move quite swiftly once it starts:

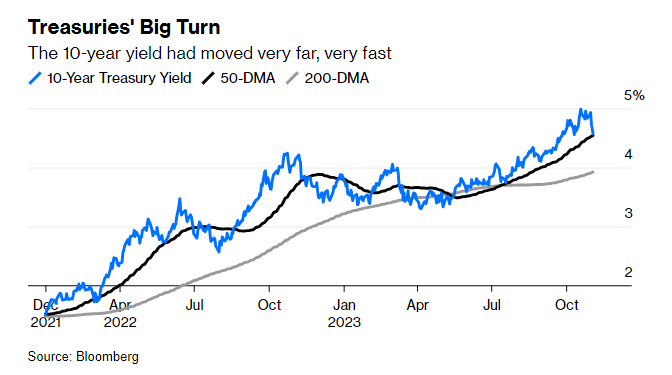

That’s quite a move. As for the critical 10-year Treasury yield, it had looked as though the bond selloff was overdone. Last week’s surge back into bonds has left the 10-year yield challenging the short-term support of its 50-day moving average. A few more days of traffic in the same direction are needed before we can clearly say that the upward trend is over:

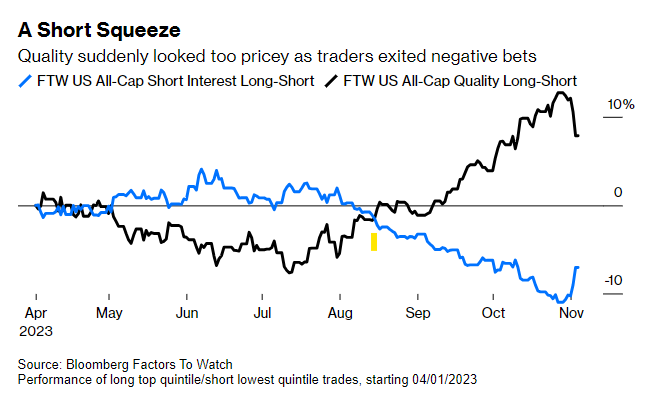

Within stocks, Bloomberg’s Factors To Watch service reveals that there was a surge out of defensive “quality” stocks with well-defended balance sheets and earnings, which are viewed as conservative investments in difficult times, while there was a big rebound in the stocks that had been most heavily sold short, meaning that investors were betting against them. Anyone who had been assuming imminent disaster decided they needed to rethink swiftly:

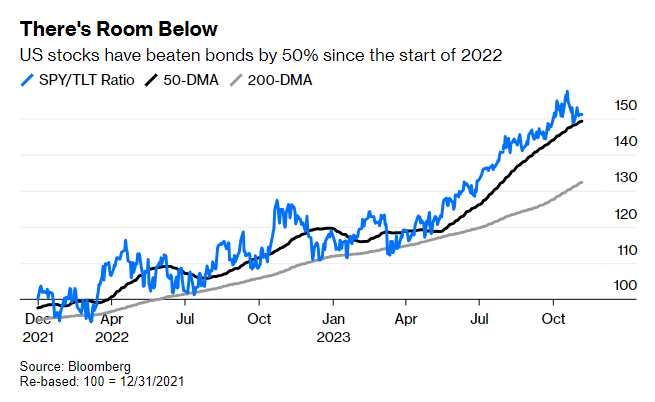

The essential asset allocation choice between stocks and bonds remains more finely balanced than ever. Proxied by the main exchange-traded funds tracking the S&P 500 and Bloomberg’s index of Treasuries dated 20 years or longer (universally known by their tickers SPY and TLT), we find that the dramatic upward trend for stocks compared to bonds remains intact, but that the last few days have brought it back to test short-term resistance, despite the rise in stocks. If bonds were to gain more, there is a lot further for this ratio to move:

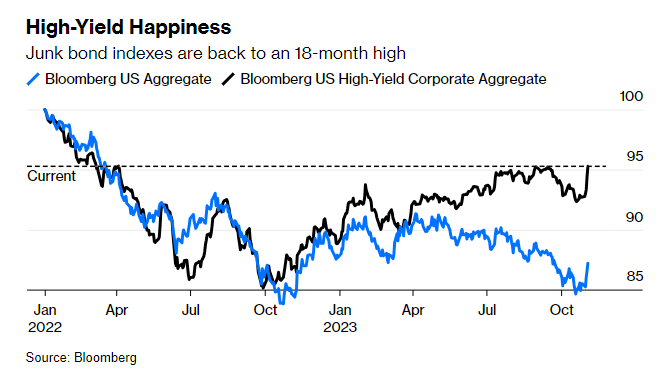

It’s in the credit market that the response to last week begins to stretch credulity. Corporate credit, and in particular high-yield credit, or “junk,” has held up remarkably throughout the rising rate period that began in January last year. Credit indexes have finally begun to give way in the face of evidence of tightening lending standards, bankruptcies and delinquencies. In the case of high-yield, all of that decline has been reversed. Bloomberg’s US high-yield index is back as elevated as it’s been since April last year:

The economy is slowing, and the monetary authorities think conditions are tight and are worried about letting them get too tight — so buy speculative credit?

To try to understand how this can possibly be reconciled, we need to dive into financial conditions.

Conditional Surrender

Monetary policy, Powell has reminded us, works through tightening financial conditions and deterring economic activity. That takes time to work its way through the system. Or, in the words of Milton Friedman, it has a lag.

Of late, Powell has been emphasizing the work that tighter conditions — principally the higher 10-year yield — are doing for the Fed. That cheered many by suggesting that higher rates wouldn’t be necessary, and that’s probably been confirmed by the events of last week.

However, various problems remain. If there’s a monetary lag, and rates have been rising for 18 months, the implication is that conditions could get tighter for another 18 months as well. If that does happen, how exactly will it be possible to avoid a recession? How do you define what conditions matter in any case? And if it’s the market that has made conditions tighter, it follows that it can also make them looser. Buying things like credit because tight conditions mean there will be no more rate hikes is self-defeating, as it loosens conditions again.

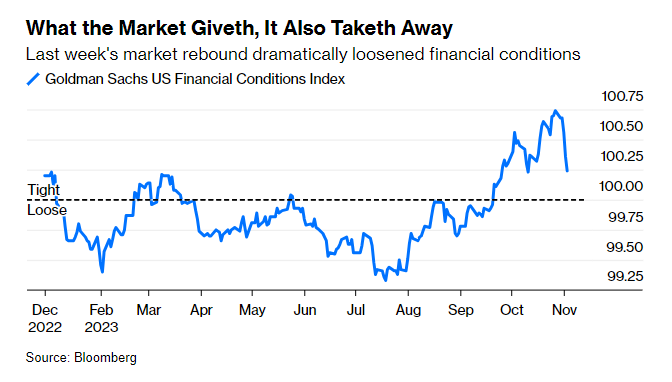

For a demonstration of this last effect, here’s the Goldman Sachs financial conditions index. It’s defined by its inventors as “a weighted average of riskless interest rates, the exchange rate, equity valuations, and credit spreads, with weights that correspond to the direct impact of each variable on GDP.” It suggests that conditions were as tight as they had been all year to start last week, and since then they’ve dropped more than half of the way toward neutral:

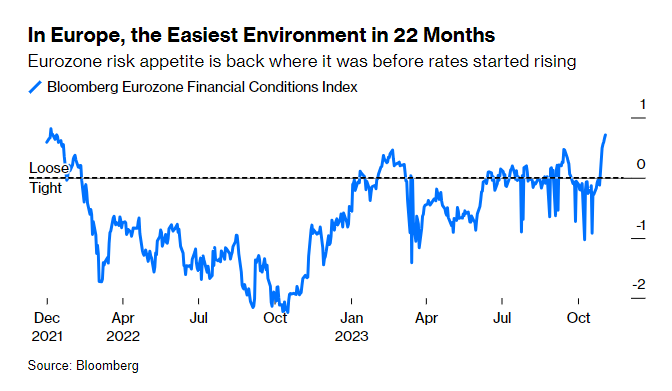

This is a classic example of what the financier George Soros calls “reflexivity” — the capacity of markets to create their own reality, and not just reflect an external state of affairs. For an even more startling example, Bloomberg’s own measure of eurozone financial conditions suggests that last week saw a flip from tight to loose. Despite everything, financial conditions are no longer particularly limiting, and are as loose as they were at the end of 2021, before the tightening cycle began:

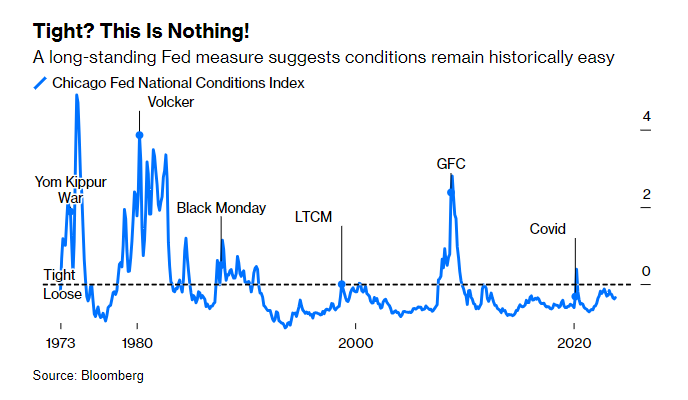

Moving on to definitions, the longest running index in use today is kept by the Chicago Fed. It’s constructed to have an average value of zero, and then its scale is measured by the number of standard deviations by which conditions differ from that average. This means that the index grows less variable over time, but the general pattern is that conditions are usually somewhat easy — and that when they tighten, they can get very tight indeed. But that doesn’t apply at present. Looking back 50 years, we discover that national financial conditions were actually looser than average at the beginning of last week:

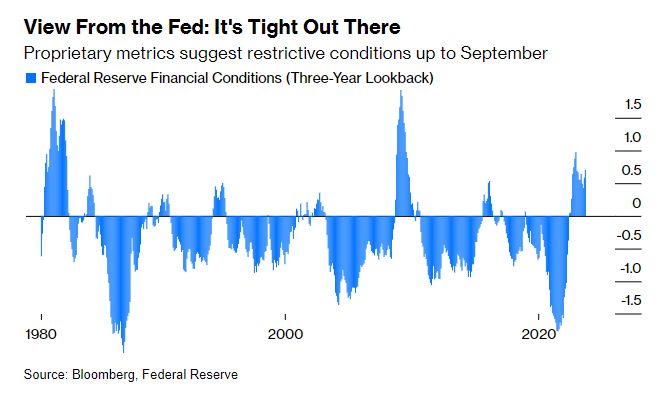

That suggests that monetary policy still isn’t biting. But the Fed has a more recent internal benchmark, explained here, which is published monthly and currently available until the end of September. It’s based on seven variables: the fed funds rate, the 10-year yield, the 30-year fixed mortgage rate, the triple-B corporate bond yield, Dow Jones’ total stock market index, the Zillow house price index, and the nominal broad dollar index, and is weighted according to the impact they’re each having on the economy. The index shows the impact that the change in these measures in the preceding three years will have on gross domestic product over the next year, and it suggests life was getting difficult by the end of September:

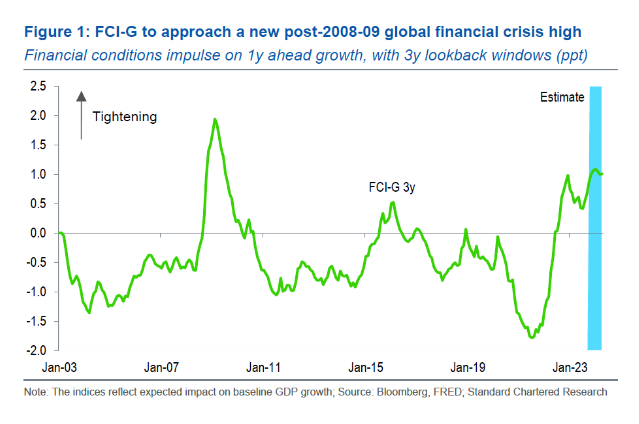

At the point that Powell gave his press conference last Wednesday, this index must have looked terrible. Steven Englander of Standard Chartered PLC has published his own estimate of where that measure is now — and by his reckoning, conditions are as difficult as they’ve been since the crisis of 2008-09. With asset prices at the level they started this week, the index implied that conditions were tight enough to take 1.1 percentage points off baseline gross domestic product growth in the year ahead:

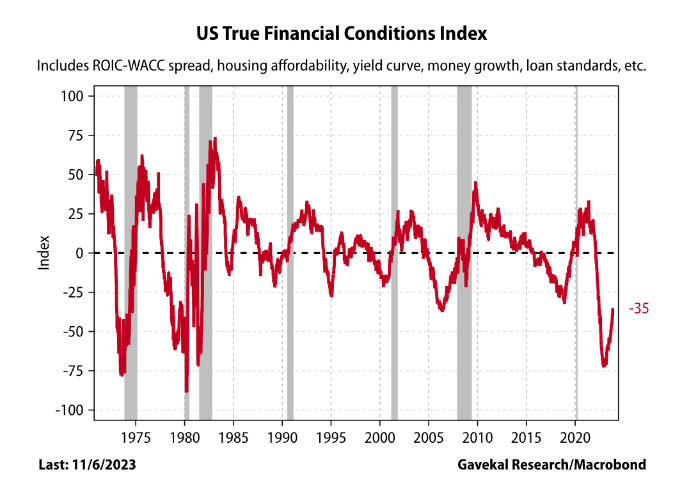

If we look at the “true financial conditions index” kept by Will Denyer of Gavekal Research, which focuses on issues such as the gap between the return on and cost of capital, credit standards and housing affordability, rather than on market measures that he regards as more of a measure of risk appetite, we find an almost totally opposite picture. Conditions have been easing in the last few months, but remain tighter than even in 2008. That implies that a recession is harder to avoid than many now seem to assume:

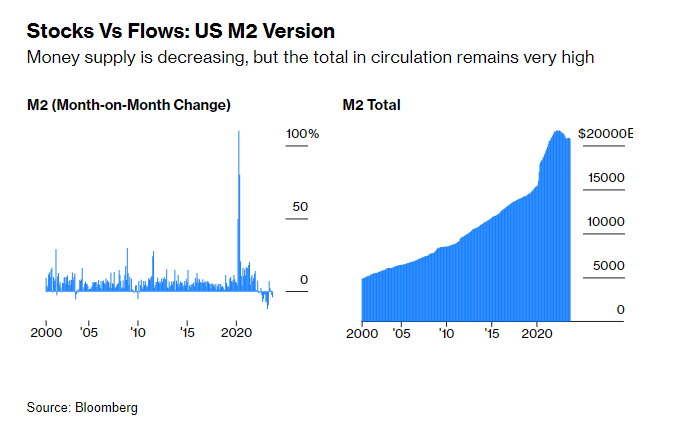

On this analysis, conditions are already tight enough to ensure that bonds are a buy, but that equities aren’t. The work has been done and we just need to wait now for the inevitable economic slowdown that follows. Finally, we come to one of the central economic debates of the last half-century: monetarism. Is the supply of money in circulation something that responds to other conditions, or does it drive them? A test case is unfolding thanks to the incredible increase in the money supply (shown in the charts below by the broad “M2” definition) during the pandemic. That has led in the last year to several out-and-out declines in the money supply, month on month, something that hadn’t happened before, while the growth of the total stock of M2 remains intact:

If it’s the change at the margin that matters, then the risk of recession appears acute. Indeed, it might be unavoidable. But the amount of excess money in the system has evidently been enough to contain this problem for much of the year. It’s effectively extended the “lag” that Friedman saw before monetary policy had an effect. How long until tighter money has the dreaded lagged effect?

For the short term, this suggests that a big market rally could be self-defeating, although the way investors piled in last week suggests that there’s every chance of a surge in risk assets from now until the end of the year. For the longer term, it begins to look like a Catch-22: If things are as tight as some believe, then bonds are a big buy and equities aren’t. If they’re in fact as loose as others imply after last week’s drama, the risk is of another swerve at some point in the near future as central banks feel obliged to up the ante again and push up yields.

© 2025 Bloomberg L.P.