By John Authers

Sept. 23, 2022

We’re living through arguably the most truly global attempt to tighten financial conditions in memory. This is shifting the tectonic plates beneath the world economy, and threatens dangerous developments in society and in politics as we all try to adapt. And yet what strikes the eye after a week of market landmarks and aggressive interventions by central banks is the continuing discord.

The post-Volcker, multi-generational trend of low yields is over./Photographer: Stefani Reynolds/AFP/Getty

There’s a broad acknowledgement that the future involves tighter conditions to combat inflation, and with it an elevated risk of recession; but even though these sobering things are now widely accepted, deep differences remain. This is an attempt to sum up the most important developments after an epochal week.

The Ice Age Is Over (Really)

The downward trend in 10-year Treasury yields that has persisted ever since the Fed under Paul Volcker slew inflation is over. There have been false alarms before. Dig through the archives and you’ll find I wrote at very great length about what appeared to be the end of the trend during a bond selloff as long ago as 2007. But that market seizure triggered the credit crisis, which would bring Treasury yields to previously unimaginable lows. High inflation in 2022 will make that prohibitively difficult to repeat.

There are many ways to measure a trend, and I want to resist any temptation toward pseudo-scientific technical analysis. But on any sensible approach, the trend has been broken. If Jerome Powell and the Fed succeed as they hope, and replicate Volcker, then maybe they can start another downward wave. But that will be a new trend, not a resumption of this one.

The following chart (a screenshot from the terminal because I had problems with my graphic software, for which I apologize), shows various trend lines that might link the high points for the 10-year yield since Black Monday in 1987. Any version of the line has been breached. And critically, after a series of lower highs, this cycle has left the yield significantly higher than at the top of the previous cycle. Traders can no longer rely on the post-Volcker momentum behind falling rates, which explains why the Fed feels the need to replicate its illustrious former chairman:

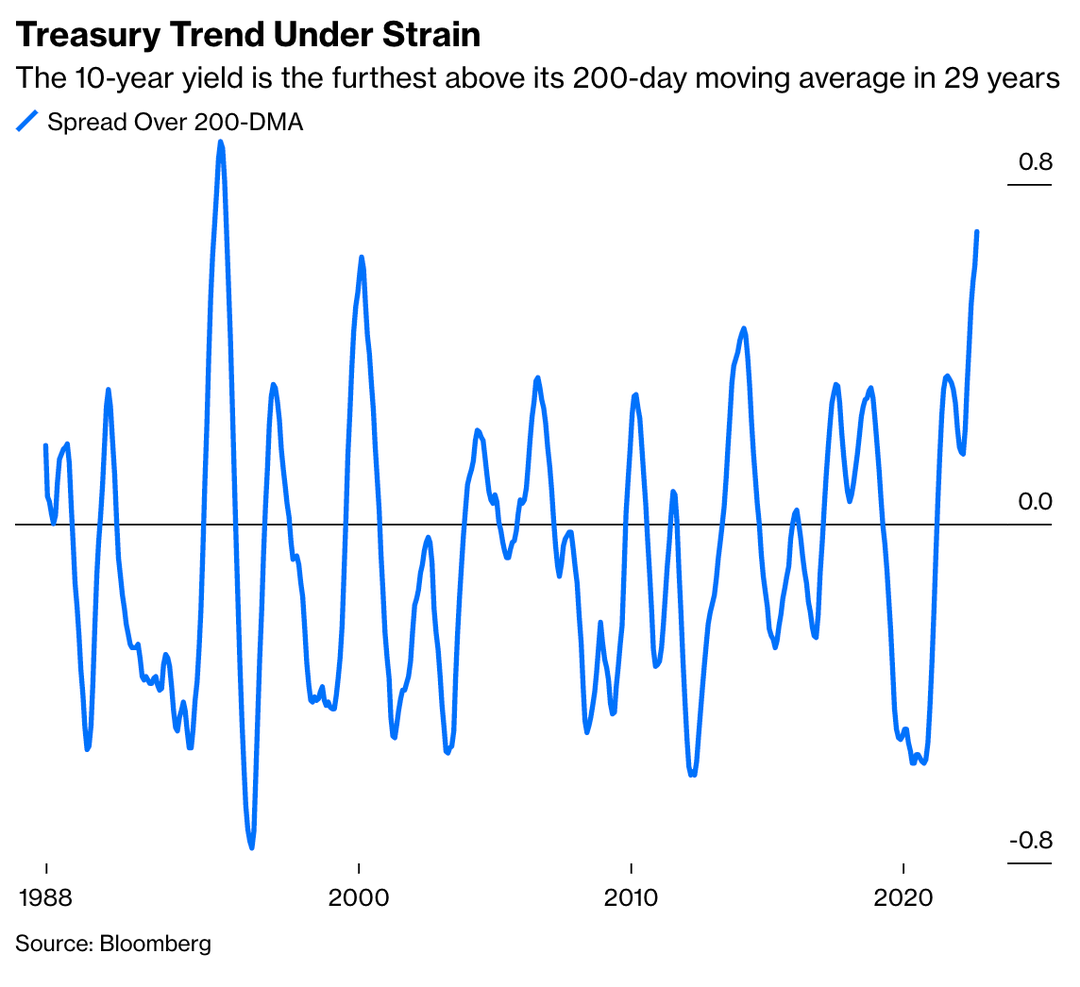

The yield is now well above its 200-day moving average, a measure of the long-term trend. To illustrate that more clearly, this is how the gap between the yield and the moving average has shifted since 1987:

The 10-year yield broke slightly further above the long-term trend in 1994, which not coincidentally was the last time the Fed — under Alan Greenspan — surprised the market with an aggressive series of rate hikes. But it’s still a big deal that the most important measure in finance is the furthest above its trend in 28 years.

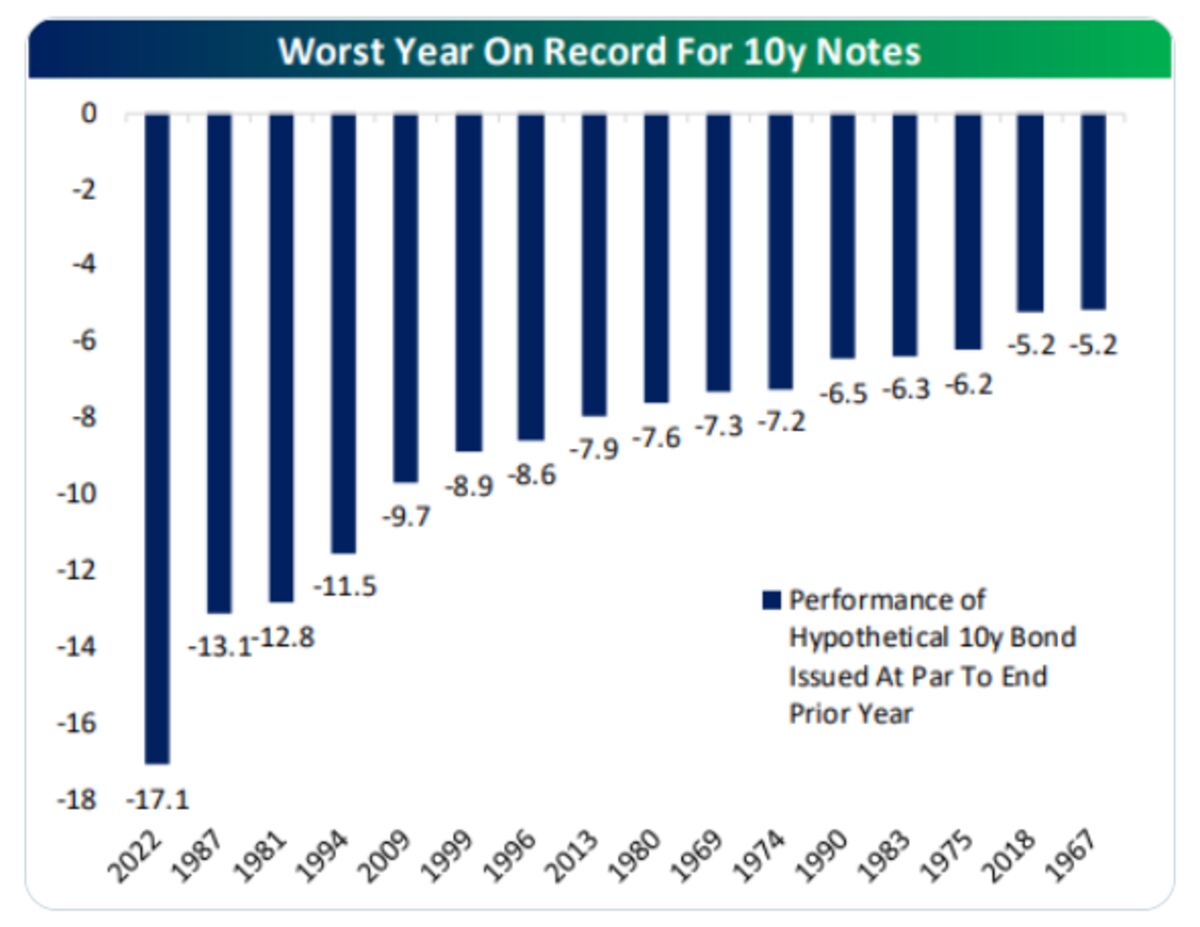

For another indicator that the ice has been broken, just look at the losses that this selloff has inflicted. The joys of bond math mean that a rise in yield from a lower level can inflict a greater dent on the price, and that shows up in spades this year. The following chart, from Bespoke Investment Group, shows the biggest calendar-year losses that holders of 10-year bonds have suffered since 1961. With 2022 not quite three-quarters over, this is already the worst year for bond investors in six decades:

For a final critical indicator, read the latest opinions of Albert Edwards. Societe Generale’s chief investment strategist is (slightly unfairly) known as an inveterate perma-bear. He’s certainly been negative on equities for a long time, but he’s also (correctly) been bullish about bonds. His thesis, inspired from his time in Japan in the 1990s, was that the US and the rest of the developed economies faced an “Ice Age” in which yields stayed permanently low. So psychologically, it means a lot that he is now prepared to declare the Ice Age over. He thinks bond yields will keep rising. But don’t worry, that doesn’t mean that he’s gone positive on stocks:

The theme of secular stagnation which underpinned our Ice Age thesis for so long has been dealt a fatal blow as politicians begin to shed their fiscal shackles. Until recently, economic ideology had prevented them breaking free from fiscal austerity. That had caused central bankers to fill the economic void with super-expansionary monetary policy. Those days are now over and aggressive fiscal activism reigns supreme, most visible currently in the UK. This will bring higher growth, higher inflation, and higher interest rates across the curve. The party for investors is over. The Great Melt will not only melt the ‘Ice’ in ‘Ice Age,’ but investor returns are set to melt away too.

Inversion Submersion

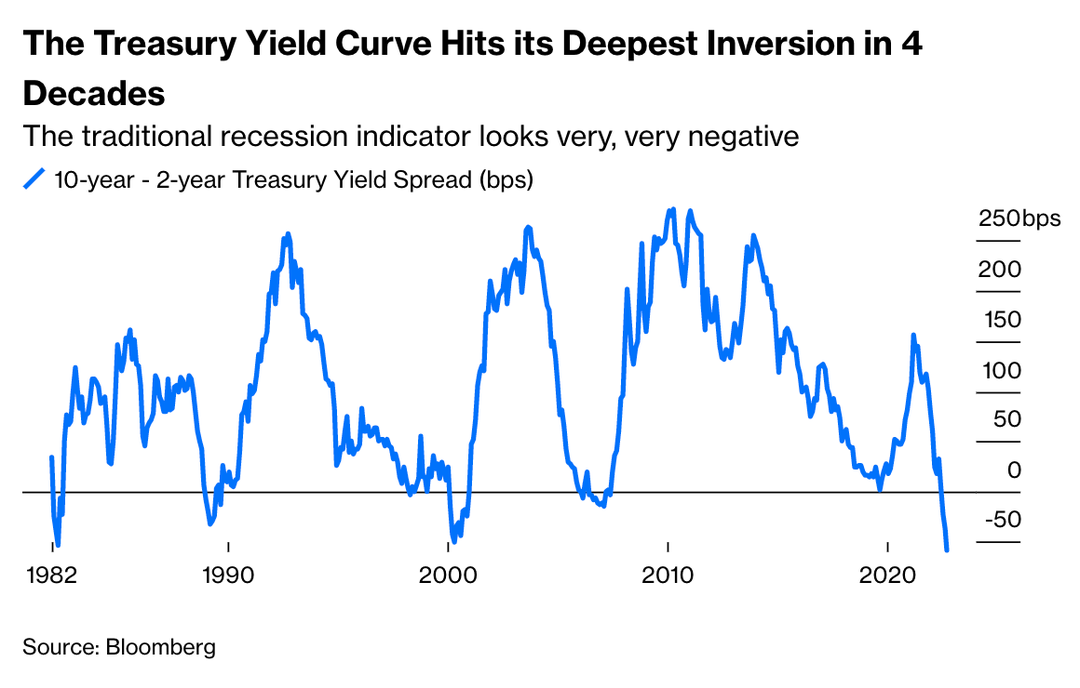

One more reason to think that things have changed is that we now have an extreme inversion of the yield curve. In other words, the 10-year yield is lower than the two-year yield, even though it would usually be higher to account for the extra uncertainty that goes with investing further into the future. When the curve inverts, it’s often regarded as a recession indicator. It’s also a sign that the market thinks that the Federal Reserve is about to overdo it, raising rates a lot in the short run to drive slower growth in the longer term.

It’s thus pretty significant that the yield curve has now inverted to the extent of more than 50 basis points for the first time in more than 40 years (since, not coincidentally, Volcker was hiking rates to fight inflation):

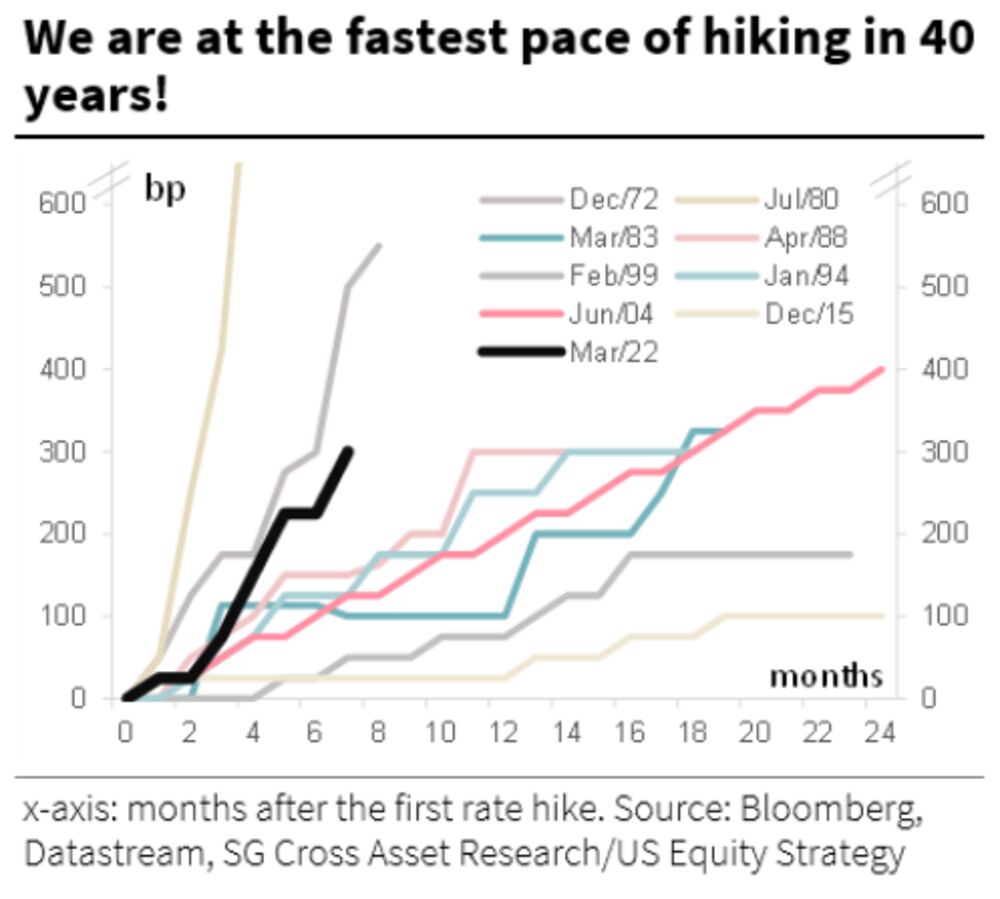

The curve has steepened slightly since I drew this chart, but the market’s basic message remains. Why is the bond market so concerned? As this chart from SocGen shows, this is now the fastest tightening, in terms of the number of extra basis points added, since Volcker in the summer of 1980. Interestingly, this tightening is slightly slower than the one overseen by Arthur Burns (to whom history has been much harsher than Volcker).

In terms of the last four decades, it really is different this time. It’s not so different from what came before, but the rules that most people now active in markets have learned to live by no longer apply.

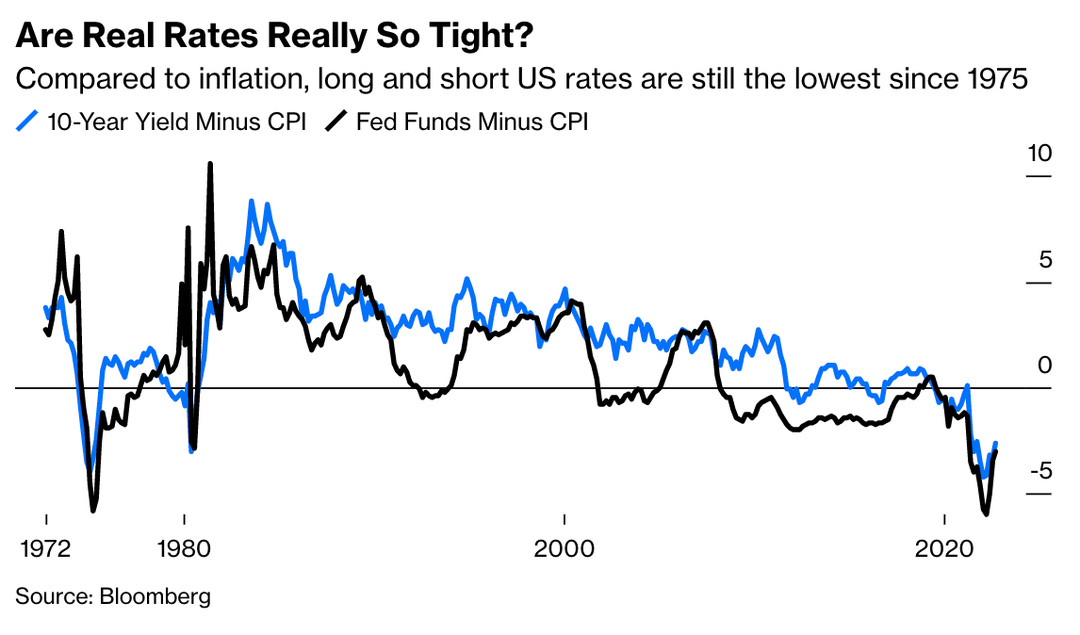

How Tight Are We Really?

There are any number of views on how far the Fed will have to hike rates from here, but the critical issue is to reach a point where rates are meaningfully restrictive. A rule of thumb is that the fed funds must rise to exceed the inflation rate. If that’s true, then this episode has a long way to run. Both the fed funds rate and the 10-year yield are still far below the level of inflation, so on this basis real rates are still negative. Neither of these key rates has been so low compared to headline consumer price inflation since the Burns era in the mid-1970s:

Keeping a United Front

Yesterday I commented on the wide spread of opinions within the Fed on where they think the fed funds rate will be in 2024. That’s concerning. Then on Thursday, the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee split three ways over what the rate should be now; one member voted for a 25 basis-point hike, three voted for 75 basis points, and five — the minimum needed for a majority — opted for 50 basis points. That’s not exactly clear. As a result, gilt yields surged, and yet the pound managed to drop to yet another 37-year low against the dollar.

The UK also has a specific issue with the clash between fiscal and monetary policy. The BOE is prompted to tighten, despite the grim economic conditions, because the new government under Liz Truss says that it’s about to embark on a fiscal splurge, focused around tax cuts and handouts to alleviate the energy crisis. Are they going to coexist, or will the UK’s financial authorities cancel each other out?

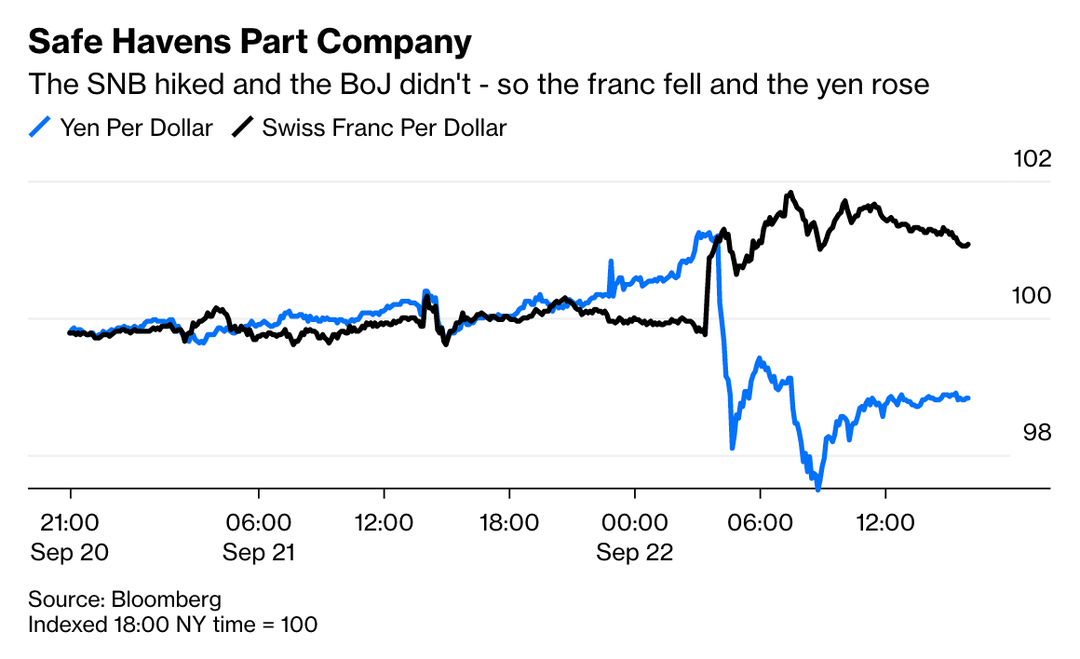

Japan suffers on a variation of that dynamic. The Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance are traditionally at loggerheads. In the wake of the Fed’s rate hike, the BOJ reaffirmed that it was doing nothing at all to change its monetary policy, which remains the most lenient in the world. That prompted the ministry to make its first intervention to prop up the yen in 24 years, pulling the currency back to its level of early last week.

Meanwhile, the Swiss National Bank met and agreed to a hike of 50 basis points, meaning that it leaves the ranks of countries with a negative base rate. This was a big deal. Switzerland is a sanctuary of low inflation in the middle of Europe, and its currency continues to be regarded, like the yen, as a haven. But thanks to the intervention in the yen, and an environment in which other central banks were hiking even more aggressively, the yen rose and the franc fell. Yes, that is the exact opposite of what should be expected to happen when the yen was backed by a central bank that stood pat, and the franc was backed by a historically important hike:

The direction of travel is clear, but the differences between central banks are still intense and prone to drive big market reactions. It’s a hazardous environment.

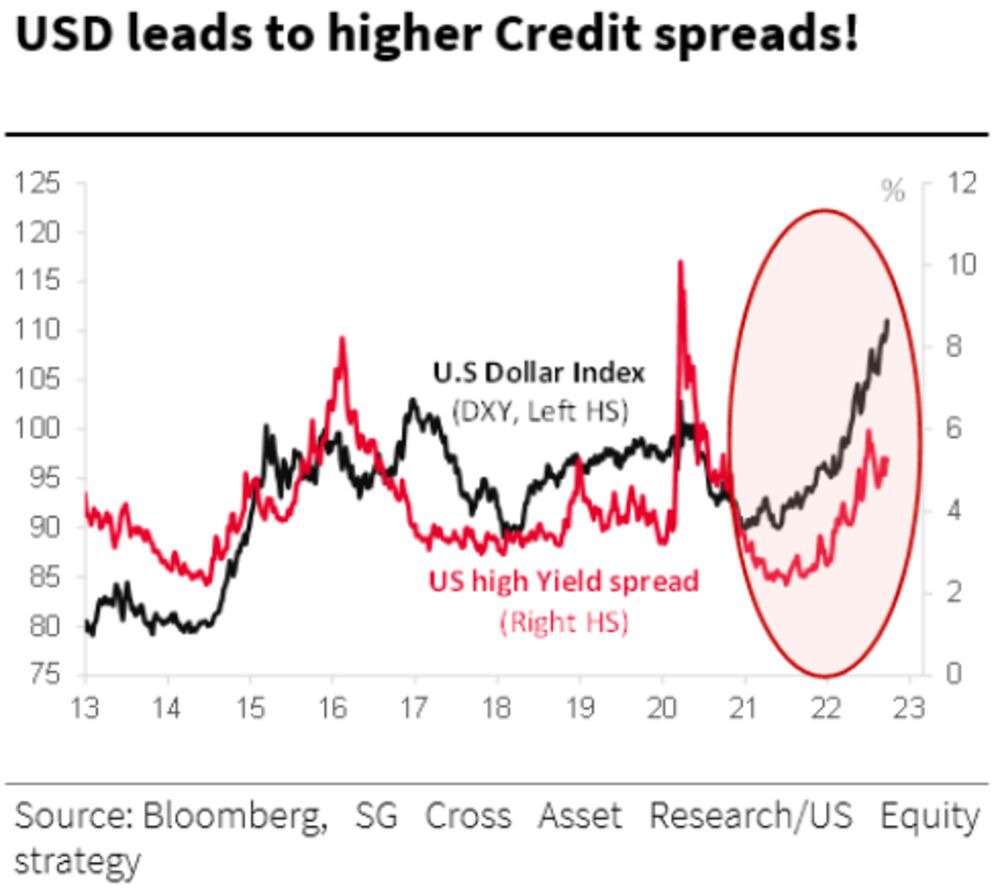

What About Credit?

A stronger dollar (and this is the strongest in 20 years) generally means a tougher environment for US credit. Exporters find it harder to make their sales, and so on. But so far in 2022, the credit market has been a dog that didn’t bark. High-yield spreads — the extra risk that is perceived in weaker credits — have risen, but not by anything like the extent that might be expected given the strength of the dollar, as shown in this chart from Societe Generale:

What happens if and when the credit show finally drops?

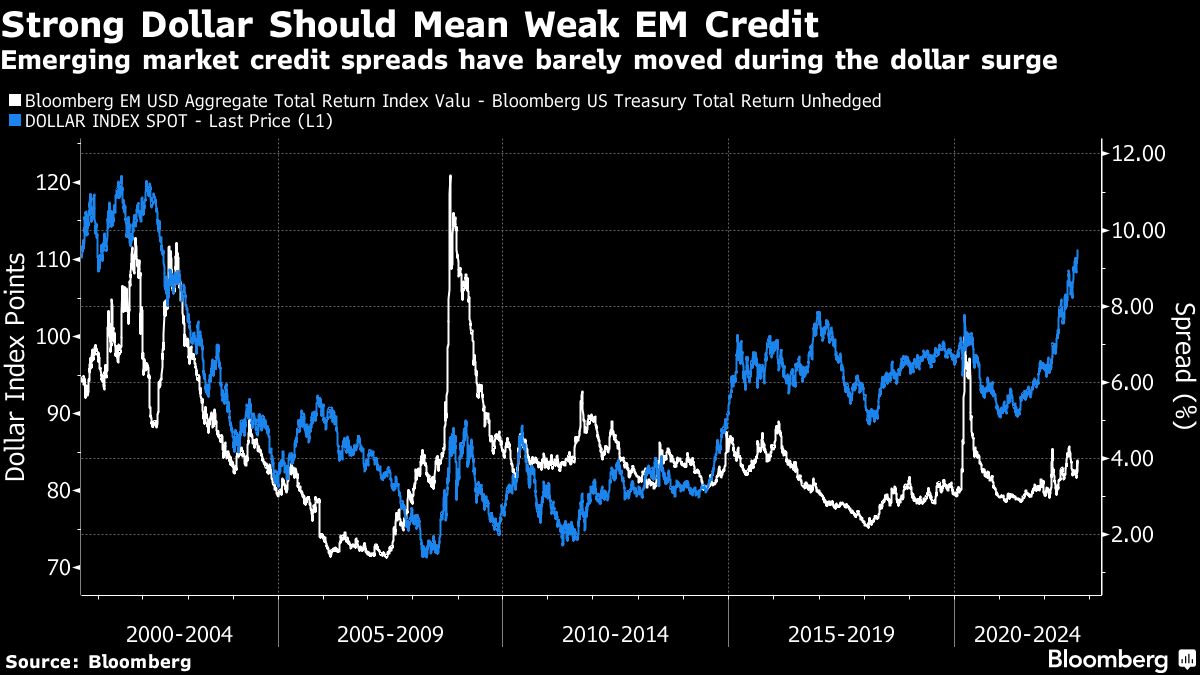

Emerging Concerns

Similar concerns apply to emerging markets. Their currencies have been under pressure for a while, and their central banks in many cases started hiking many months before the Fed started its own campaign. A stronger dollar is straightforwardly bad for dollar-denominated EM credit as it makes it directly more expensive to repay. A stronger dollar tends to mean higher EM credit spreads. And yet EM debt has hardly weakened as the dollar has surged. As this chart shows, the relationship between the dollar and EM spreads is very similar to the pattern for US high-yield spreads:

This is a risk to which many are very alert. Emerging markets have worked to build domestic local currency markets and reduce their reliance on dollar debt over the last decade, but the fear of a possible developing world credit crisis remains real.

Earnings, Please Fall

The US stock market is still above its lows from June. But can that survive the release of third-quarter earnings when companies report their profitability and forward guidance — or the lack thereof? Third-quarter estimates have been revised lower, as generally happens, but remain quite high. Analysts still expect S&P 500 companies’ profits to grow next year, a view that many money mangers have said is too optimistic. Here’s April LaRusse, head of investment specialists at Insight Investments:

Companies are likely to continue to size down their earnings expectations going forward… Clearly they’re also going face higher financing costs because the central banks are saying, ‘We need to put rates up more.’

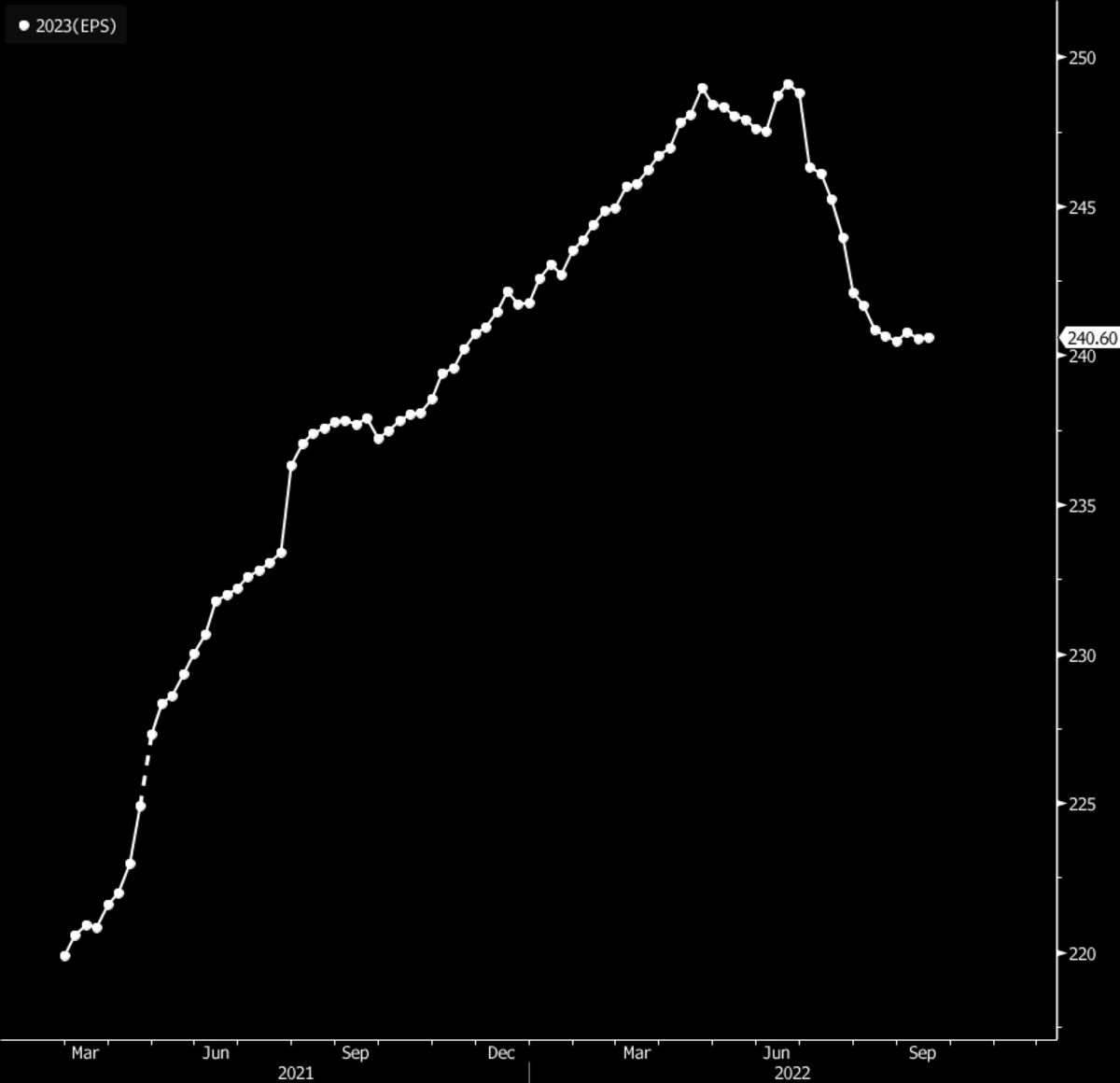

S&P 500 earnings estimates for 2023 have retreated since June, according to a Sept. 16 note published by Bloomberg Intelligence’s Wendy Soong. For this year, the senior associate analyst expects S&P 500 earnings per share to be at $226.50, down 0.7% from peak, while S&P 500 EPS for next year has taken a bigger hit, down more than 3% from the midsummer peak.

Major firms including Ford Motor Co., FedEx Corp., General Electric Co. as well as chemical companies like Eastman Chemical Co. and consumer-goods firms like spice maker McCormick & Co. have recently issued profit warnings. The worst part? The gloom and doom still isn’t priced in. Here’s Lauren Goodwin, economist and portfolio strategist at New York Life Investments:

With so much recent volatility, investors have been asking if bad news isn’t already priced in. I’d argue that the market reaction to early earnings releases suggests that slowing economic activity is nowhere near priced in. Earning estimates are likely to continue their decline until we see a bottoming in leading economic indicators. We are not there yet.

Adding further headwind is the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act, the sweeping tax, climate and health-care measure signed into law last month, as my colleague Felice Maranz wrote. JPMorgan Chase strategists led by Dubravko Lakos-Bujas expect the law to chip away around $4 to $5 per share in 2023, due in large part to the 15% minimum tax for companies with more than $1 billion of book income per year and the 1% excise tax on stock buybacks.

John Authers' Points of ReturnGet John Authers' daily sharp analysis on the market's ups and downs.Sign up to this newsletter

With a hawkish Fed now accepted, the equity market’s focus will move on to focus on earnings, a point made on Bloomberg TV by the veteran equity strategist Abby Joseph Cohen, who is now a professor at Columbia Business School. The S&P 500 closed at the lowest since June, with many analysts predicting it will test the June lows. And Lori Calvasina, head of US equity strategy at RBC Capital Markets, writes that the need to cut forecasts may remain an overhang on stocks:

Earnings sentiment has already been hit quite hard, with the rate of upward EPS estimate revisions near non-tech bubble/GFC/pandemic lows over the summer (~30%). Normally in major periods of stress in the stock market, major bottoms in the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 are established 3–6 months before EPS forecasts start to turn positive again. It’s also worth noting that the rate of upward revisions has started to heal and was close to 50% again in early September.

The much-feared earnings recession did not materialize in the results for the second quarter, which helped propel the summer stock market rally. Can Corporate America repeat the trick in the third quarter?

— Isabelle Lee

Survival Tips

People give central banks much of the blame for today’s economic problems, but I feel that many of them are merely trying to fill a vacuum left by politicians who aren’t prepared to grasp the nettle and tell their voters what they don’t want to hear. It wasn’t always thus. I’m grateful to Albert Edwards for reminding me of a video clip, which I dimly recall from my childhood, of Britain’s Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan imparting painful truths to his party conference. Callaghan hasn’t gone down as one of the great prime ministers; he took over the job only when his predecessor (who’d been diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s) resigned. He went on to lose to Margaret Thatcher in 1979. But he was a decent man who inherited an impossibly difficult situation, and took solid steps toward sorting out the UK’s problems. With hindsight, some even date economic “Thatcherism” from this speech, when he accepted the case for fiscal discipline.

Viewed from 2022, the clarity and the honesty with which he speaks almost hurts. This is an intelligent and sensible man calmly telling his people the truth. Here is one of the key passages:

We used to think that you could spend your way out of a recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting government spending. I tell you in all candor that that option no longer exists, and insofar as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step.

If you feel like despairing at the hideous state of current politics, close your eyes and dream of politicians behaving like that again. An Abraham Lincoln or a Winston Churchill would be nice. But even a Jim Callaghan would be such an improvement.

Enjoy the weekend.

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.