By Sam Goldfarb and Peter Santilli

April 27, 2021

What do investors expect from a post-pandemic economy?

They generally seem quite optimistic. Stocks stand near records. Meanwhile, yields on U.S. government bonds and certain derivatives are suggesting the economy will be strong enough for the Federal Reserve to start raising short-term interest rates by 2023 and keep going for a couple of additional years.

In essence, investors are betting that a combination of government stimulus and coronavirus vaccines can drive a quick return to the economy that existed just before the pandemic. Back then, a decade of slow, steady growth had finally started to produce meaningful gains for even low-skilled workers.

Still, investors seem skeptical of an even-better outcome in which the economy’s capacity for growth is lifted by favorable demographic changes, technological innovation or government investment. Here is a closer look at investors’ bets on the economy:

MONETARY POLICY

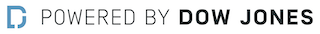

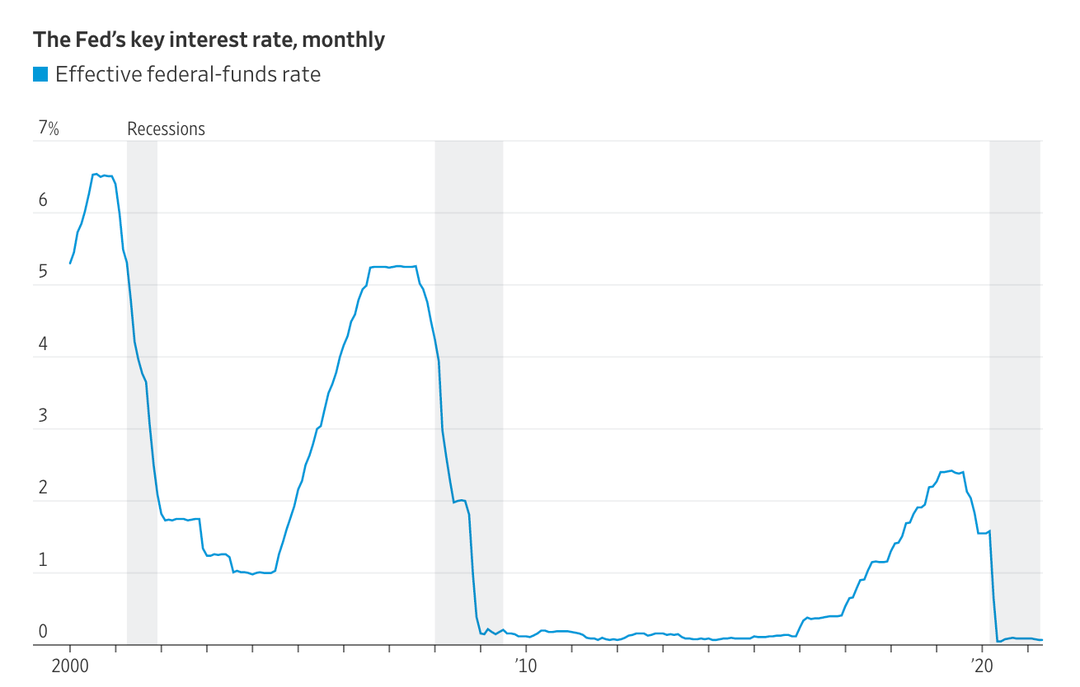

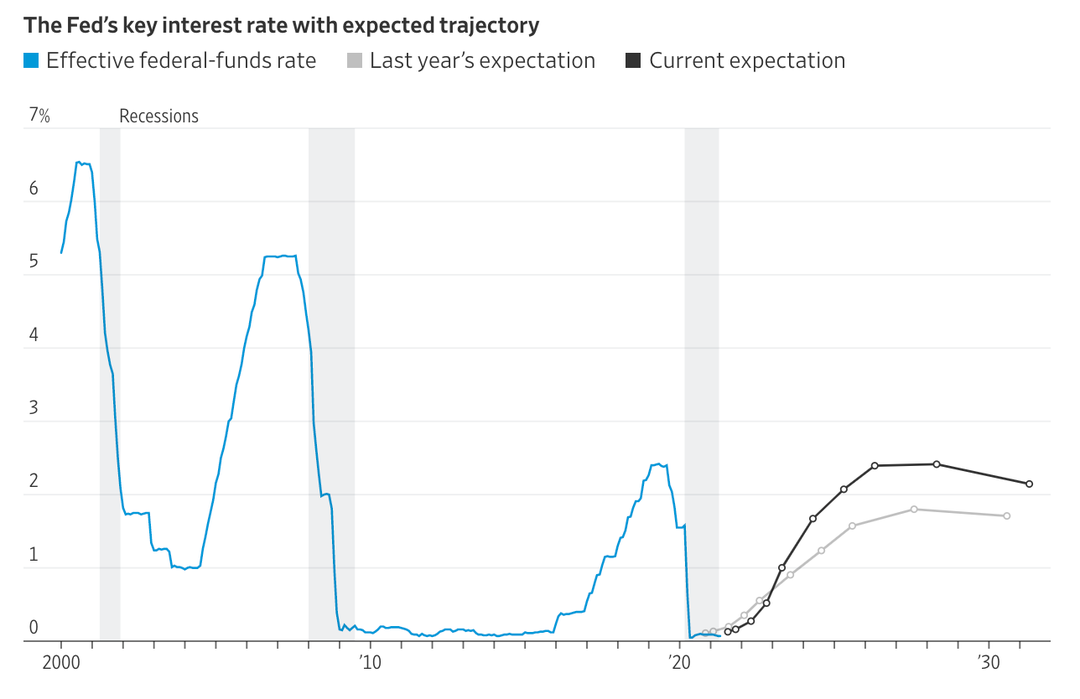

The federal-funds rate set by the Fed is a measure of the economy’s strength. When the economy is stronger, the Fed raises the short-term rate to make sure inflation doesn’t rise too far above its 2% annual target. When it is weaker, the Fed cuts rates to lower borrowing costs for businesses and consumers and boost economic activity.

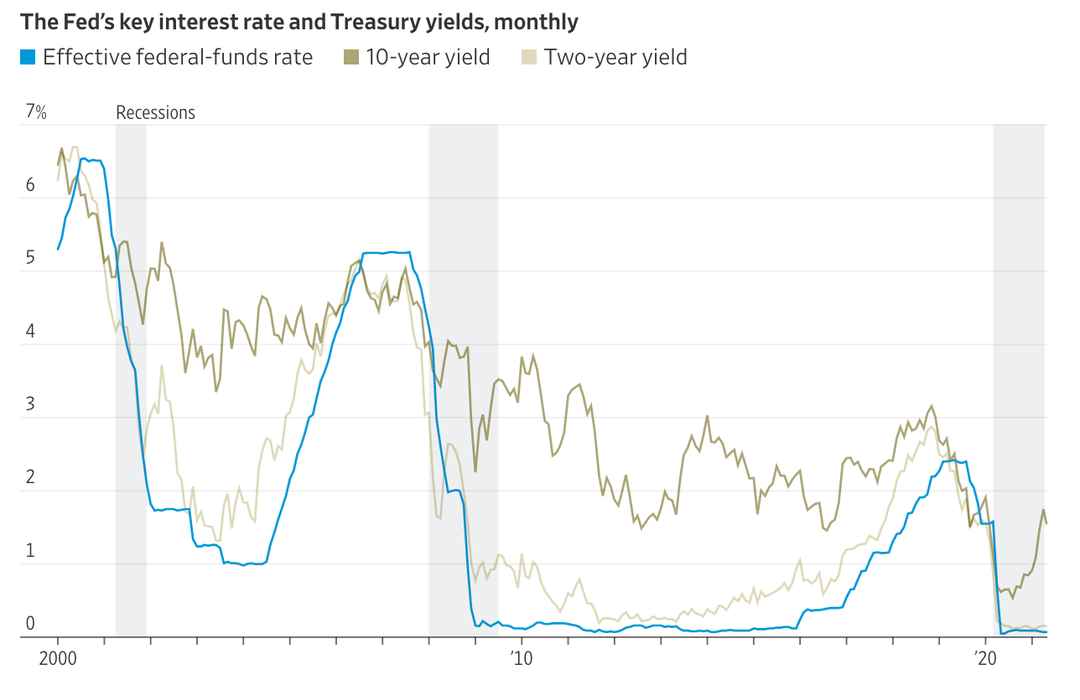

TREASURY YIELDS

The yield on a U.S. government bond largely reflects investors’ expectations for the fed-funds rate over the life of the bond. The 10-year yield fell to a record low last year, signaling short-term rates near zero for years to come. The yield’s rebound this year reflects bets on a strong economic rebound and higher rates.

RATE EXPECTATIONS

Investors wager on the future level of the federal-funds rate in the overnight index swap market. Last summer, investors thought the short-term rate would be slow to rise in coming years and would level off below its pre-pandemic peak, reflecting a deeply damaged economy.

GROWING OPTIMISM

The current expectation is more optimistic.

FAST RESTART

Notably, investors think the Fed will be able to raise rates much sooner than it did after the 2008-09 financial crisis and at a similar pace.

PLATEAU ENVISIONED

But investors also think the Fed won’t raise rates higher than it did before the pandemic. The Fed’s terminal rate has dropped in recent decades, reflecting in part an apparent decline in sustainable economic growth. Investors now envision a new version of the pre-pandemic economy—not a fundamentally stronger one.

INFLATION AND MONETARY POLICY

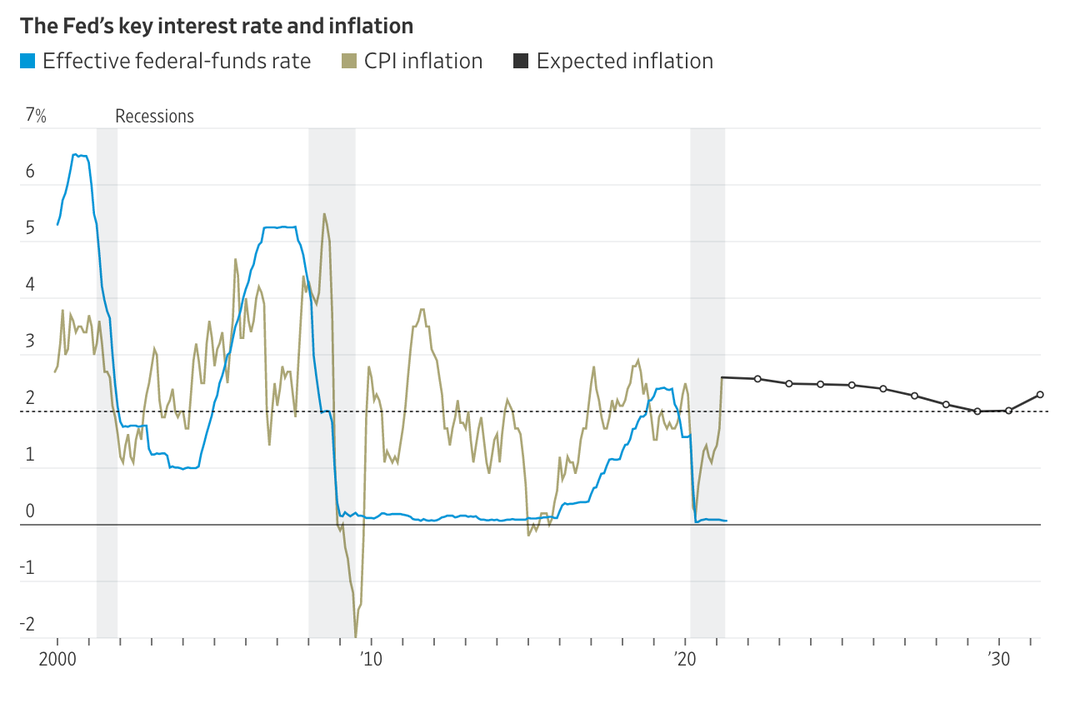

Lackluster inflation has been a defining characteristic of the U.S. economy in the years since the 2008-09 crisis. The widely tracked consumer-price index has struggled to stay above the Fed’s 2% target. The Fed’s preferred gauge, the personal consumption expenditures price index, has typically shown even less inflation.

INFLATION OUTLOOK

Investors’ expectations for inflation—as defined by the consumer-price index—over the next 10 years can be gleaned from the difference between nominal and inflation-protected U.S. Treasury yields. Investors are hardly expecting runaway inflation. But they expect sustained inflation around the Fed’s target, even as the central bank raises interest rates.

Investors’ optimism about the future is apparent in stocks as well as bonds. Major indexes have continued to climb this year even as Treasury yields have shot upward, another sign of investors’ confidence that the economy can withstand higher interest rates.

That isn’t always the case. In late 2018, the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note climbed as high as 3.2% with investors anticipating more interest-rate increases from the Fed. Stocks fell sharply and fully recovered only when Fed Chairman Jerome Powell signaled easier money policies.

This year, there have been some stock-market jitters as yields climbed. High-growth tech shares in particular are seen as more vulnerable to higher rates because their valuations are based more on future earnings. But the market has still managed to power forward, and even the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index has bounced back recently—another sign that investors don’t expect a fundamentally different economy or rate environment than existed before the pandemic.

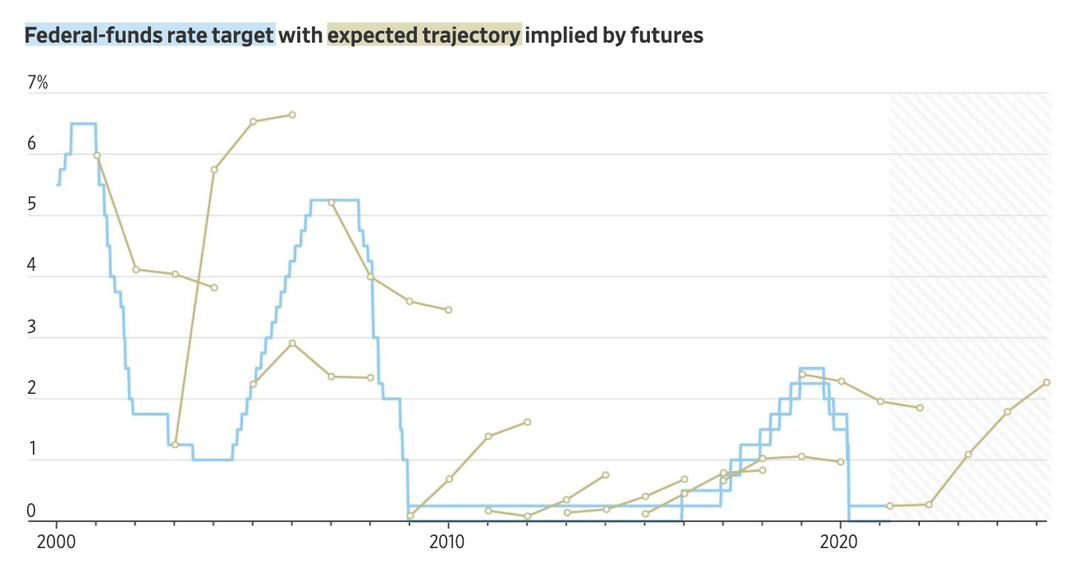

Investors have a decidedly mixed record of predicting the future, having repeatedly overestimated what short-term interest would be in recent years.

Investors may have a natural bias toward preparing for higher rates since they stand to lose money on Treasurys if yields rise, said Roberto Perli, head of global policy research at Cornerstone Macro. That tendency could be even more pronounced when short-term rates are at zero and there is essentially only one way for them to move, given repeated statements from Fed officials that they don’t like the idea of negative rates.

Mr. Perli said some investors think: “I don’t think the Fed is really going to raise rates next year, but if it does my portfolio is going to lose a lot of money, so it’s sensible for me to hedge this risk.”

Notes: Expectations for future interest rates are adjusted to account for term premium—the estimated amount of extra yield investors demand to hold longer-term bonds, or comparable derivatives, rather than a series of short-term bonds. Investors buying a 10-year Treasury note, for example, might estimate what the average federal funds rate will be over the next decade, but then demand additional compensation for the risk that that rate could be higher. Term premium can also be negative if investors are more worried about interest rates undershooting their forecasts than exceeding them.

So-called breakeven rates, determined by the difference between nominal and inflation-protected Treasury yields, aren’t necessarily perfect representations of investors’ inflation expectations. They may be distorted by investors demanding compensation not just for expected inflation but the uncertainty of the inflation outlook. Investors may also demand some additional yield to own inflation-protected Treasurys because the securities trade less frequently than ordinary Treasurys.

Sources: Dow Jones Market Data (Treasury yields, federal-funds rate); Cornerstone Macro (federal-funds rate expected trajectory, expected inflation); Bureau of Labor Statistics via Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (inflation)

Write to Sam Goldfarb at sam.goldfarb@wsj.com and Peter Santilli at peter.santilli@wsj.com

Copyright 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.