By Shane Shifflett and Danny Dougherty

March 27, 2023

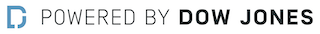

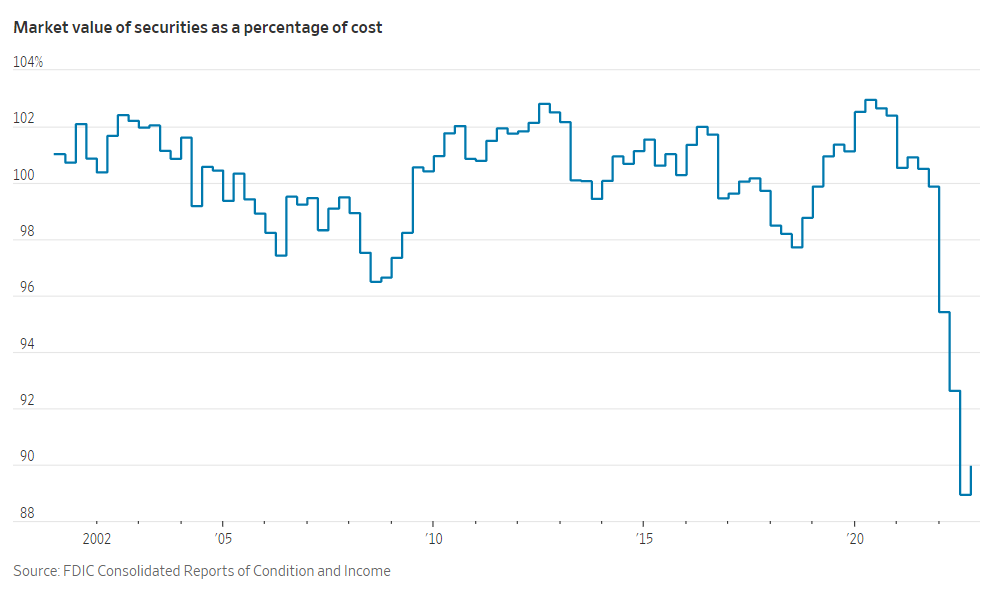

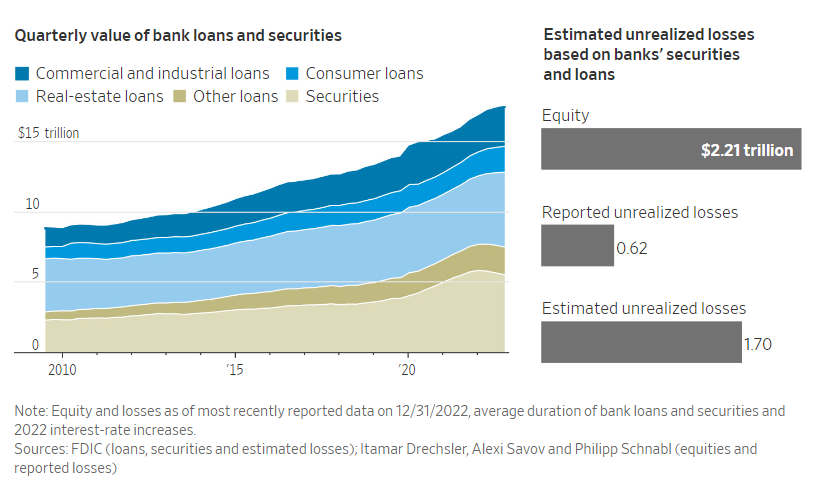

The sudden collapse of Silicon Valley Bank was driven in part by assets that lost value when interest rates rose from near zero. Higher rates will continue to weigh on banks’ balance sheets. They will also cause problems in other parts of the economy.

Banks lost money on securities sensitive to interest rates such as Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities. Those losses will grow if rates keep going higher. If, as the Federal Reserve hopes, those rates slow the economy to ease inflation, the banks could face other losses. One risk is commercial real estate, where owners of half-empty office buildings might struggle to pay their debts. That would hurt commercial mortgage-backed securities, which are already declining in price.

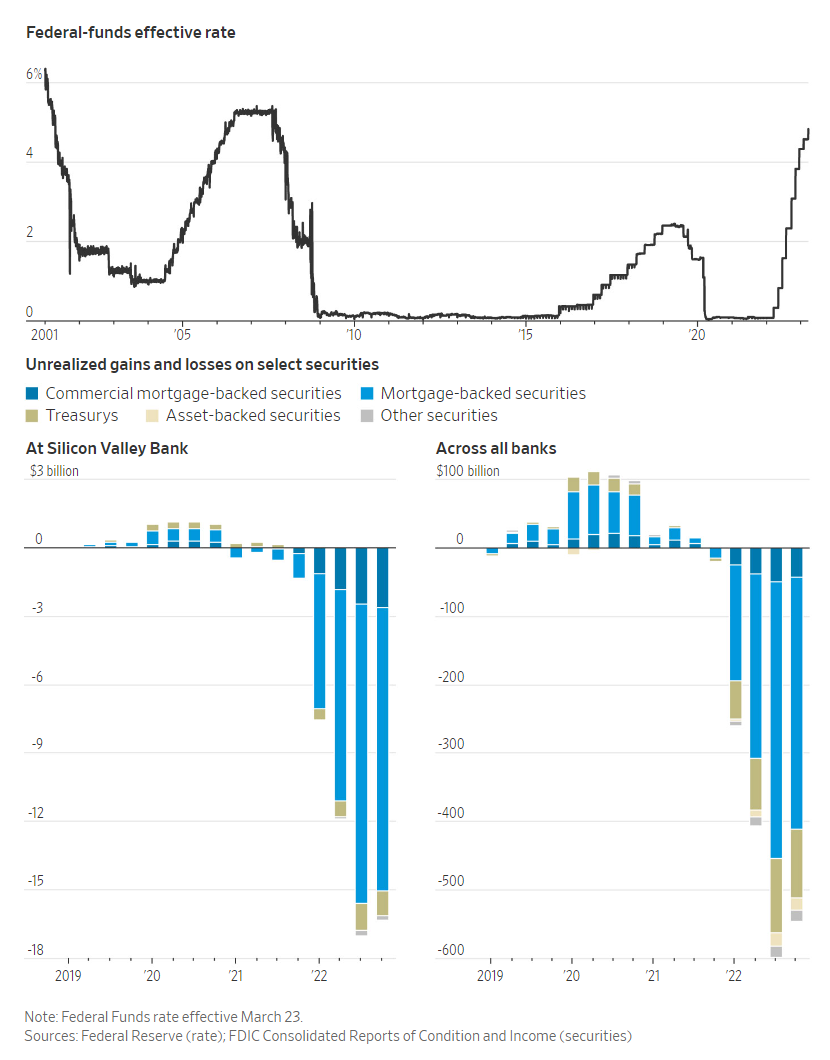

Deposits are increasingly uninsured

Fickle depositors pose another risk. Banks enjoyed an influx in deposits during the pandemic as U.S. households accumulated about $2.3 trillion in so-called excess savings in 2020 and 2021, according to the Fed. Businesses, too, stashed cash at banks, in part because it was impossible to earn a safe, decent yield.

But a growing share of the funds deposited with banks exceeded the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s insured limit of $250,000. Nearly $8 trillion of deposits at the end of 2022 were uninsured, up nearly 41% from the end of 2019, according to reports filed with the FDIC that were analyzed by The Wall Street Journal.

Nearly 200 banks would be at risk of failure if half of uninsured depositors pulled their money from the banking system, according to a paper published by economists from the University of Southern California, Northwestern University, Columbia University and Stanford University.

Mortgages are rate-sensitive

Banks took those deposits and invested in mortgage-backed securities valued at $2.8 trillion at the end of 2022, or about 53% of securitized investments, helping to fuel a pandemic housing boom.

Homeowners gained a collective $1.5 trillion in equity in 2020 from a year earlier as prices surged, according to CoreLogic. Sales of previously owned homes were down 22.6% in February from a year earlier, while the national median existing-home price dropped for the first time in 11 years.

Under accounting rules, banks don’t have to recognize losses on most of their holdings unless they sell them. Unrealized losses on banks’ mortgage-backed securities were $368 billion at the end of 2022, according to FDIC data analyzed by the Journal. Many fear that rising interest rates will force other regional banks to sell their holdings at a loss as well, potentially pushing prices lower. To address that risk, the Fed will offer loans at 100 cents on the dollar to banks that pledge assets such as Treasurys that have lost value.

Commercial real-estate risks are rising

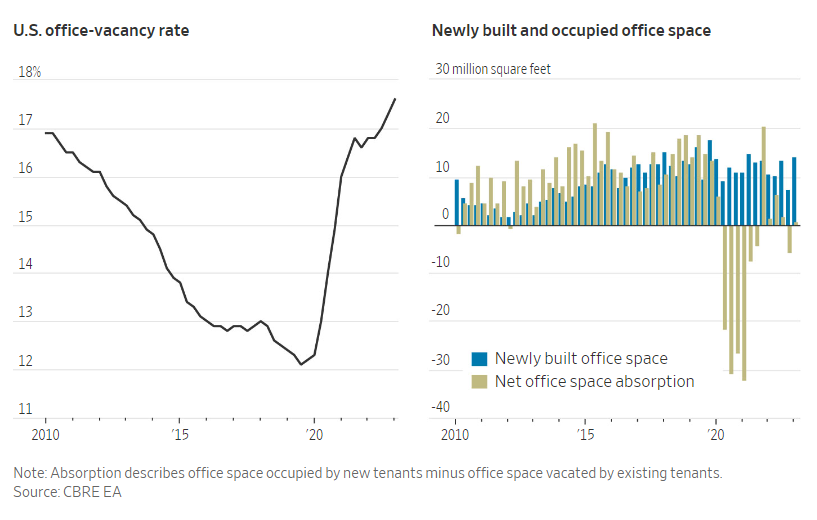

Unrealized losses on commercial real-estate debt securities reached $43 billion last quarter, FDIC data show. Banks held $444 billion of these securities at the end of 2022.

But landlords are under pressure as businesses scale back on space because employees are working remotely. Office-space vacancy rates are expected to keep rising through 2024, according to the commercial real-estate services and research firm CBRE EA.

Banks’ exposure could be multifaceted

Landlords also take out loans to purchase properties, and small banks hold $2.3 trillion in commercial real-estate debt, according to Trepp Inc., or roughly 80% of commercial mortgages held by banks.

“The combination of lower operating income generated by office properties and a higher cost of financing, if they persist, would be expected to reduce valuations for these properties over time,” said FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg. “This is an area of ongoing supervisory attention.”

At the end of last year, banks held $17.5 trillion in loans and securities, while equity in the banking system was more than $2 trillion, FDIC data show. Estimated unrealized losses on total bank credit reached $1.7 trillion, according to a recent paper by New York University Prof. Philipp Schnabl and co-authors.

Shadow-banking issues are hard to quantify

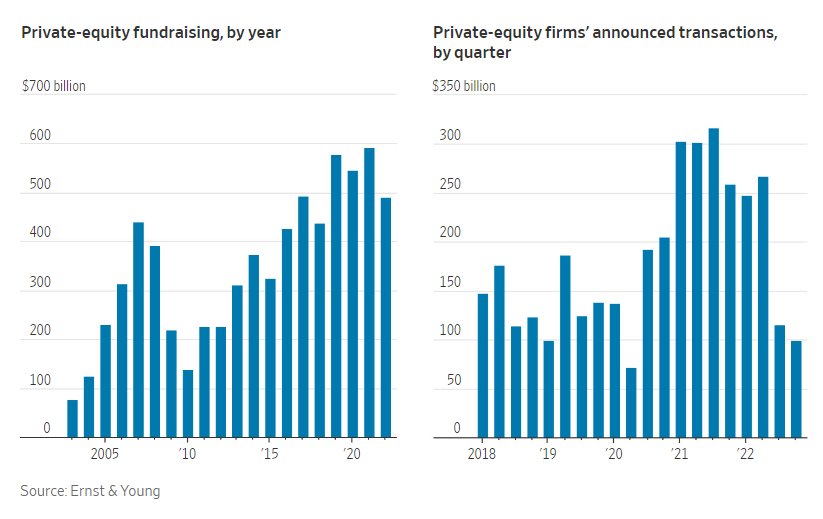

Risks could lurk elsewhere in the financial system. Private-equity firms often raise funds or borrow cash to buy assets such as companies and real estate. They can offer investors higher returns often by making risky bets that could get more expensive. On the positive side, no one mistakes these investments for insured bank deposits. On the negative side, private equity and private debt are black holes in the financial system.

Private markets’ total assets under management reached $11.7 trillion last June, according to McKinsey. Private-equity firms have raised record amounts of cash in recent years and announced nearly $730 billion in investments, according to Ernst & Young LLP.

Write to Shane Shifflett at shane.shifflett@dowjones.com and Danny Dougherty at danny.dougherty@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.