Ian McGugan

Sept. 14, 2020

It is high time for retirees and pension funds to dial back their exposure to “dead-weight” bonds, according to one of Canada’s leading pension experts.

Keith Ambachtsheer, the president of KPA Advisory Services in Toronto and director emeritus of the International Centre for Pension Management at the University of Toronto, argues that bonds at their current, dismal yields can no longer deliver the returns needed to fund retirements – not unless you assume savings rates well above what most of us would regard as practicable.

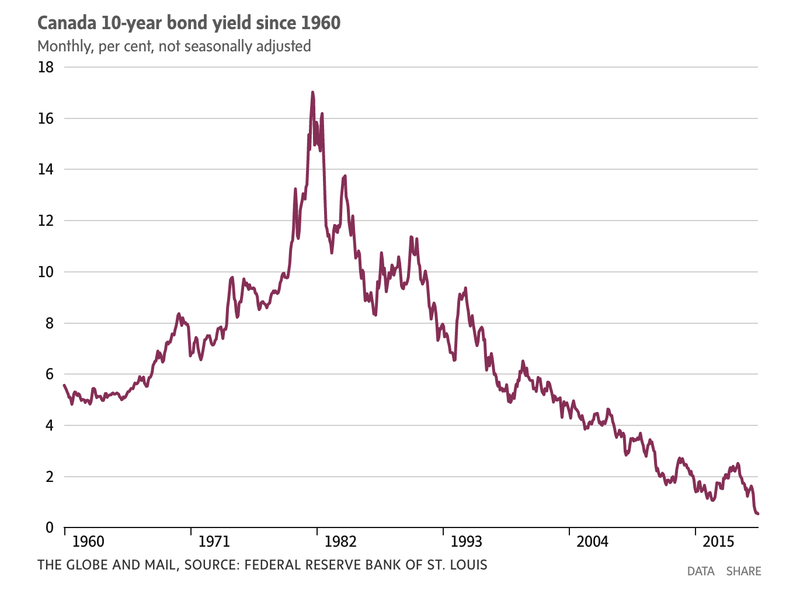

“Twenty years ago, inflation-indexed bonds offered a real yield of 4 per cent,” Mr. Ambachtsheer wrote in a report. “Today their yield is not just zero, but actually negative.”

The upshot is that bonds are “dead-weight investments” that “currently have no role” to play in the investment policies of continuing pension plans, he said.

In an interview, he suggested that similar logic applies to many personal portfolios. Bonds can no longer reliably generate much cash flow for retirees, so savers hoping to generate steady income from their holdings have to contemplate the notion of cutting back on their exposure to bonds.

His comments demonstrate how the long fall in interest rates in recent years is disrupting some of the most sacred tenets of investing.

For decades, pension funds and private investors regarded a portfolio composed of 60 per cent stocks and 40 per cent bonds as the sturdy all-terrain vehicle of the investing world. A 60-40 portfolio was supposed to deliver decent returns in just about any investing environment.

That proposition now seems in doubt. Benchmark 10-year Government of Canada bonds are yielding barely half a percentage point in annual payout. After adjusting for the corrosive effect of inflation on purchasing power, a typical bond is poised to deliver a negative return in real, or after-inflation, terms.

This challenges the logic underlying a 60-40 portfolio. When yields were substantially higher a decade or more ago, bonds acted both as a buffer against stock market weakness and as a source of real returns in their own right.

No longer. At their current yields, bonds are likely to actually subtract from a portfolio’s long-run buying power.

With interest rates already so low, bonds may not serve as much of a buffer, either. Yields have little room to move even lower because they are already bumping up against zero. As a result, bond prices (which move in the opposite direction to bond yields) have limited room to gain even if the world slumps back into economic turmoil.

So what should investors hold instead of bonds? Solid dividend-paying stocks, Mr. Ambachtsheer suggests.

Consider Unilever Group, he says. The giant British-Dutch consumer-products company pays a dividend yield of just over 3 per cent. History suggests it can grow that dividend at 1 per cent or more a year.

In theory, a stock’s long-term return should be equal to the sum of its dividend yield and its dividend growth rate. If so, Unilever should be able to deliver a real return of at least 4 per cent a year. This is far in excess of what most bonds are now paying.

Investors who select a cluster of similar dividend payers are likely to fare much better than people who stick to a traditional diversified portfolio, Mr. Ambachtsheer asserts. He suggests pension funds should shift to using a portfolio of dividend-paying stocks as their benchmark, or reference portfolio, in years to come.

“Rather than the traditional 60-40 stock-bond policy mix, such a well-diversified stock portfolio has become the reference portfolio for sustainable going-concern pension plans aspiring to deliver adequate inflation-linked pensions at affordable contribution rates into the indefinite future,” he wrote.

There are, to be sure, some objections to this viewpoint. One is whether pension funds and individuals are prepared to deal with the occasional but devastating paper losses that go along with holding an all-equity portfolio.

Mr. Ambachtsheer acknowledges that staying calm during crises requires strong nerves, both for investors and for pension plan sponsors. But the evidence is clear, he argues: Thanks to the Keynesian policies put in place since the Second World War, sustained economic depressions have become a thing of the past. In the long run, stocks as a whole don’t stay in the red.

Going back to the Unilever example, investors shouldn’t focus on the spikes and dips in its share price over the years. Instead, he said, they should celebrate “the fact that Unilever’s dividends have grown steadily decade after decade with very little volatility.”

This Globe and Mail article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream.

© Copyright 2024 The Globe and Mail Inc. All rights reserved.