TIM SHUFELT| MATT LUNDY

April 18, 2020

With evidence building that the nationwide effort to contain the novel coronavirus is working, the conversation has shifted toward reawakening the economy.

This past week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the federal government is in discussions with the provinces about easing restrictions, although he warned that any significant changes are still weeks away.

The timing and method of orchestrating a recovery that won’t jeopardize the health of Canadians has become the economic policy challenge of a generation.

To stave off utter economic devastation, the federal government and the Bank of Canada have already unleashed a barrage of fiscal and monetary firepower. Ottawa has announced more than $260-billion in new spending and other assistance, and the Bank of Canada has injected more than $200-billion into the financial system. Much more stimulus is on the way.

While those measures will soften the blow, they can’t restore the economy to its former glory. Canadians who don’t have jobs to go back to won’t spend like they were before. Even workers who avoided being laid off may be in no rush to book a flight or eat in a restaurant. And for businesses that thrive on crowds, the pandemic is a potential extinction event.

“Once you hit pause on the economy, hitting unpause is not so easy,” said Trevin Stratton, chief economist at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

Economics textbooks don’t say anything about the effects of shutting down much of the global economy, or what might happen after the lockdown is lifted, because nothing like it has ever happened before. So, economists were operating more on guesswork than anything else when they began to assess the financial damage unleashed by governments around the world as sweeping social and industrial restrictions were enacted to contain the spread of the virus.

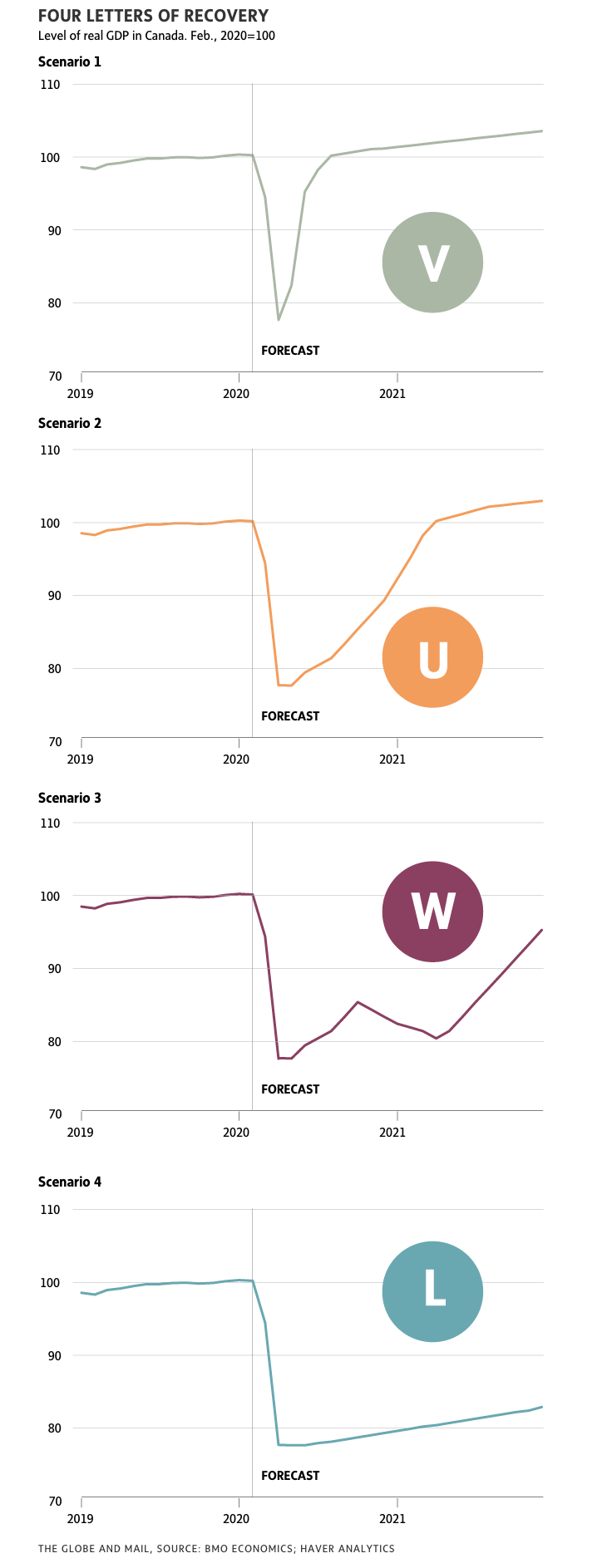

As recently as February, many forecasters envisioned a temporary disruption, followed by a swift return to precrisis activity levels. This is the coveted V-shaped recovery – a precipitous decline, came after an equally sharp rise back to full economic health.

Fighting the pandemic, however, has already exacted an immense toll, with the unfolding recession likely to be the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression, and far more severe than the one that came after the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Undoing the damage already done will be no small feat. And the longer the Great Lockdown drags on, the greater the risk of doing irreversible economic harm.

Because this recession has no historical precedent, the nature of the recovery is also shrouded in uncertainty. Besides V, the letters of the alphabet enlisted to invoke the potential shape of the recession cycle now also include U, W and L.

Whatever the shape of the recovery, one element now seems inescapable – Canada faces a long and difficult economic convalescence in the months and years ahead.

The pandemic hit crisis levels in Europe and North America so quickly, there was no time to consider the lasting effects of economic lockdowns.

Though Canada had its first diagnosed case of COVID-19 in January, until mid-March, it was pretty much business as usual. And then it wasn’t.

In a bewildering seven-day stretch, the United States suspended travel from Europe, the National Basketball Association shut down its season, the Italian health-care system was brought to the brink of collapse, global stock markets crashed, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau tested positive for the virus, and the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia declared states of emergency.

The other provinces and territories soon followed suit, closing non-essential businesses, schools, and daycares, and ordering much of the Canadian workforce to stay home.

In the early days, Bay Street was banking on a brief idling of the economy – just long enough to conquer the virus – after which everything would quickly return to prepandemic form. But now, the prospects for a V-shaped recovery have all but evaporated.

First, a sharp rebound needs a distinct and solid starting point. It also needs catalysts – several of them.

Under normal circumstances, the path out of a recession is dictated by a broad array of economic conditions, including interest rates, employment, and consumer confidence. Right now, however, government policy and public health directives remain in control of the business cycle.

In that kind of environment, traditional economic models don’t apply. Even the Bank of Canada admits to being in the dark about what lies ahead. It eliminated economic projections from its quarterly monetary policy report, released this past week, saying it can’t forecast “with any degree of confidence.”

Countries further along the curve of coronavirus infections at least offer some clues. China, for example, saw its outbreak plateau in late February and is experiencing a revival in its manufacturing and service sectors. Both are far from a full recovery but are at least expanding.

Some European countries are also easing restrictions. Even Spain, which has had the most infections of any country outside the United States, is starting to send factory and construction workers back to work.

The shutting down of productive capacity, however, can’t just be immediately reversed. How fast a factory can get back up and running depends in large part on its own supply chain. “You don’t just start up an auto plant the next day. Their suppliers are all shut down as well, so there’s a lag effect,” said Richard Powers, a business professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management.

Even before the pandemic upended global commerce, Canadian businesses were reluctant to invest. The trade war between the U.S. and China discouraged Canadian manufacturers from adding capacity. The energy sector didn’t have the option to grow, given punishing declines in global oil prices that began in 2014 and no available pipeline capacity to move additional production.

Those concerns now seem minor compared to the social and economic havoc wrought by the worst global health crisis in a century. It’s going to take a long time for Canadian businesses to regain the confidence to spend, said Beata Caranci, chief economist at Toronto-Dominion Bank. “There’s going to be some residual scarring, and I think it’ll be most evident in business investment.”

In March alone, Canada’s GDP shrunk by a stunning 9 per cent – the leading edge of what the Bank of Canada said will be the sharpest downturn on record. TD expects the Canadian economy to shrink at an annualized rate of 25 per cent in the second quarter.

Even with a big rebound in growth the second half of the year, which depends on easing of business closures and physical distancing rules, Canada will probably only recover half its lost output by the end of this year, Ms. Caranci said. A full rebound looks to be at least two years away.

As the scope of the lockdown now rules out more optimistic forecasts, the Bay Street consensus has shifted to a U-shaped recovery. In that scenario, business and social restrictions drag into the summer and recouping all of Canada’s lost output gets pushed further into the future. Just how far depends in large part on Canadian consumers, and like many businesses, they were already stretched even before the pandemic took hold.

In a typical recession, the manufacturing sector helps lead the way into a recovery. This time, with businesses big and small shuttered, the risks are heavily concentrated in services, which employ the vast majority of Canadian workers in industries such as restaurants, tourism, and real estate.

“It’s going to be the service sector that will really tell the story of the recovery,” Ms. Caranci said. Within the sector, retail is the largest industry, employing roughly 12 per cent of the entire Canadian labour force.

With Canadians urged to stay home, consumer spending has collapsed. During the week that ended March 30, credit and debit card spending in Canada fell about 60 per cent from the same period last year, according to data from Royal Bank of Canada.

One of the few areas of strength is online retail. For proof of e-commerce exuberance, look at Amazon.com Inc.'s share price, which soared to all-time highs this week as the company received huge surges in orders.

Prospects are grim, however, for many small brick-and-mortar retailers. They’re worried customers will never come back, and e-commerce giants are getting even bigger at their expense.

In Victoria, the doors are still open at Pets West, a pet-supply store, because the province deemed it an essential service. But after an initial wave of panic buying, owner Lisa Nitkin said sales have slowed considerably. “I think [the pandemic] is going to completely shift consumer habits.”

Not only are consumers physically unable to patronize many businesses deemed non-essential, but the recently unemployed may also be less inclined to do so anyway. March saw more than one million Canadians put out of work. Another 2.1-million worked less than half their usual hours.

“People are losing their jobs,” said Ethan Song, the CEO of Montreal-based clothing retailer Frank And Oak. “They’re not excited about shopping that much.” Mr. Song said he can envision a “slow, progressive return to normal,” wherein retail stores are initially open for limited hours, allowing few customers inside, and with staff under tight health protocols.

But those kinds of restrictions may be unrealistic for industries that rely on closeness between their staff and customers, like bars and restaurants. “I don’t know if it’s even possible for the whole industry to come back again,” said Vikram Vij, the restaurateur and former Dragons’ Den judge, who guessed up to 50 per cent of restaurants could fold.

There’s no guarantee that diners will return en masse to those that reopen, either. The pandemic will have a lasting effect on the psychology of consumers, the U of T’s Mr. Powers said. “People are going to continue to be very wary of their surroundings. They’re not going to change their behaviour just because of a government proclamation.”

Even before COVID-19, Canadian consumers were already looking tired. Retail sales in 2019 grew by a paltry 1.6 per cent, the slowest annual growth since 2009. The household debt burden is close to a record high, savings rates have recently plumbed multi-year lows and consumer insolvencies are on the rise.

In a public health crisis, economic policy takes its cues from public health officials. “I used to say to staff, ‘Stay two steps behind the chief medical officer of health,’” said Michael Decter, a former deputy minister of health in Ontario. “‘Whatever he or she says, that’s what we’re doing.’” Saving as many lives as possible is the only priority early on – at any cost.

Aiding the economy comes afterward. Ottawa’s more than $260-billion in assistance includes emergency spending, lending support, and tax deferrals. The Bank of Canada is continuing to pump billions into the financial system through quantitative easing – something it didn’t do during the financial crisis. The central bank buys government and corporate bonds in the open market, thereby injecting cash into the system.

But governments and central banks can only keep the country on life support for so long. “Once you get past two or three months, it’s going to be very difficult for governments to continue to backstop the entire economy,” Ms. Caranci said. Federal spending cannot prevent mass layoffs and business failures, and cities are facing deep revenue damage.

Prematurely opening the economy, on the other hand, could trigger a spike in infections and lives lost to COVID-19. This is the grim calculus now facing policymakers in Canada and around the world.

That prospect has led many forecasters to consider a possible W-shaped recovery: a tentative economic rebound, followed by a second wave of the outbreak in the fall or winter. Economists are watching China for signs of this scenario.

China’s government has slowly lifted travel restrictions and restarted factories after a disastrous first quarter. So far, nationwide infection rates remain low, but local transmission ticked up this past week, with Beijing seeing its first new cases in three weeks.

As in China, the process of getting Canadians back to work will surely be tentative, starting with low-risk sectors and regions where the outbreak has been most manageable. In Saskatchewan, which is down to one to three new COVID-19 cases per day, a plan to gradually reopen the economy could be released in the coming week, Premier Scott Moe said.

This is how the Canadian economy is going to be reinstated – slowly and incrementally. “You don’t have to have a one-day reopening of everything to get a pretty profound bounce,” said Mr. Decter, the former health official and now Bay Street fund manager.

Despite talk of a reopening and some encouraging signs, the pandemic has also forced economists to consider potential outcomes that just a few months ago were outside the realm of possibility.

Much of the economic data starting to roll out have no analog other than to the Great Depression, raising the question as to whether something similar is upon us. This is one of the prospects under an L-shaped recovery, whereby the persistence of the outbreak prevents an economic revival before a vaccine can be mass-produced, and the downturn lasts for years.

There is no formal definition for a depression, but it is generally considered to be a prolonged slump involving at least a 10-per-cent decline in real GDP. On Tuesday, the International Monetary Fund published global projections suggesting Canada’s economy would shrink by 6.2 per cent this year, before rebounding by 4.2 per cent next year.

Even within the depression category, the Great Depression stands alone for its decade of misery, which included double-digit unemployment, bank runs, and waves of credit defaults that central banks did little to try to prevent. “We think a replay of 1929 is unlikely,” Martin Roberge, a portfolio strategist at Canaccord Genuity, wrote in a report. “Contrary to 90 years ago, central banks and governments have acted sooner and bolder with various backstops.”

But a depression on a lesser scale is quite possible if the virus cannot be contained enough to resurrect the economy.

“With a depression, the first factor is depth, and the second is duration. And I don't think we're there,” Ms. Caranci said. “But if we're still in this state by the end of the summer, it certainly becomes more probable.”

This Globe and Mail article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream.

© Copyright 2025 The Globe and Mail Inc. All rights reserved.